Max Dolgicer: Opposite sides of the same coin

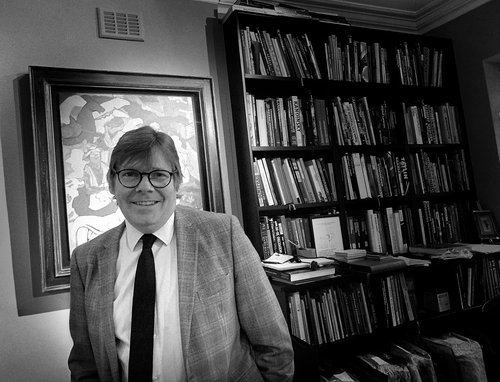

American collector Max Dolgicer, an émigré from the Soviet Union, has acquired a taste for Russian Non-Conformists and blue-chip international artists, drawing a clear line between collecting art for pleasure and for investment. Interview by Jo Vickery, leading art expert, former International Director of Russian Art, Sotheby’s.

Jet-setting IT entrepreneur and art collector Max Dolgicer was born in Soviet Latvia and later settled in New York in the 1980s, where a contemporary art scene was unfolding. A chance encounter in a restaurant where he found himself sitting beside legendary gallerist and collector Holly Solomon (1934–2002) was what inspired a decades-long passion for collecting international and Russian contemporary art, as well as interest in the digitalisation of the commercial art market.

For Dolgicer, collecting art is not a solitary activity, but much more a rich tapestry woven into his life story and family. At the outset, his collection grew from his cultural roots inspired by a personal mission. “When I began to build my collection, it was driven by what I learn about art created on each side of the Iron Curtain,” is the way he puts it.

It was his personal experience as an émigré starting out with nothing that still resonates today through his determination to support emerging artists. “Having emigrated to America with little means and almost no connections, I had to start my life from scratch in a new country. When I meet emerging artists, I’m able to empathise with them and lend some unique insight for their future careers.”

In 1989, a year after Sotheby’s legendary Moscow auction, the Soviet government appointed New York art dealer (and fellow Latvian émigré) Eduard Nakhamkin to sell contemporary Soviet art in the USA. It was then that Dolgicer first encountered contemporary art from his former homeland. Other established galleries in the city were also taking an interest in Russian art, such as Feldman and Marlborough.

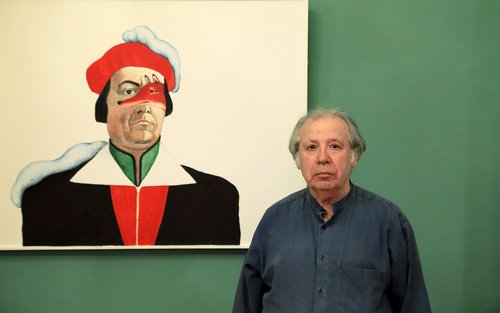

“It is undisputable that Non-Conformist art was ahead of its time and it always amazed me that artists of this era were able to produce truly contemporary art while living behind the Iron Curtain – at a time when very limited, information was reaching them from the West,” he says.

Things changed in the 1990s when numerous Russian artists settled in New York. “I don’t believe they directly influenced the New York art scene so much in terms of production and style, but I do feel they added a new dimension that was unique.”

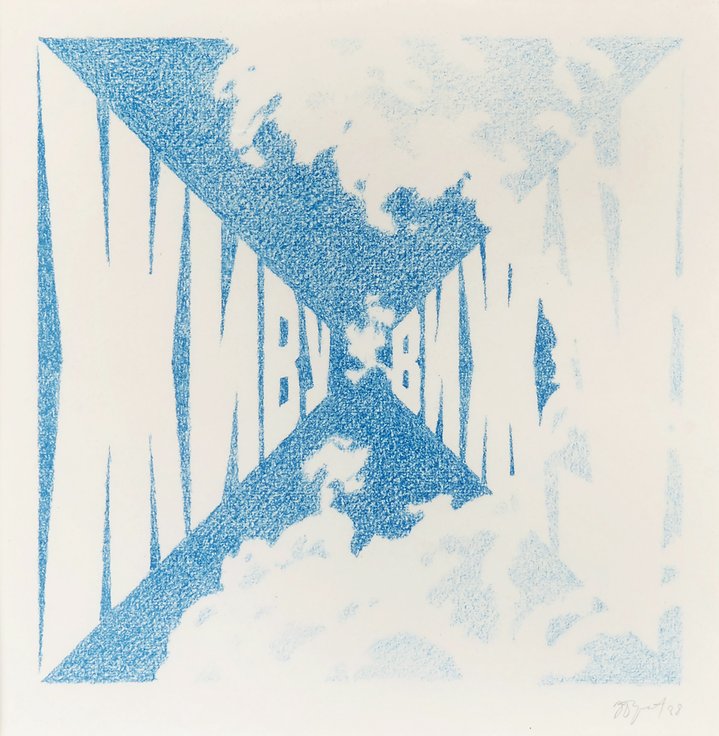

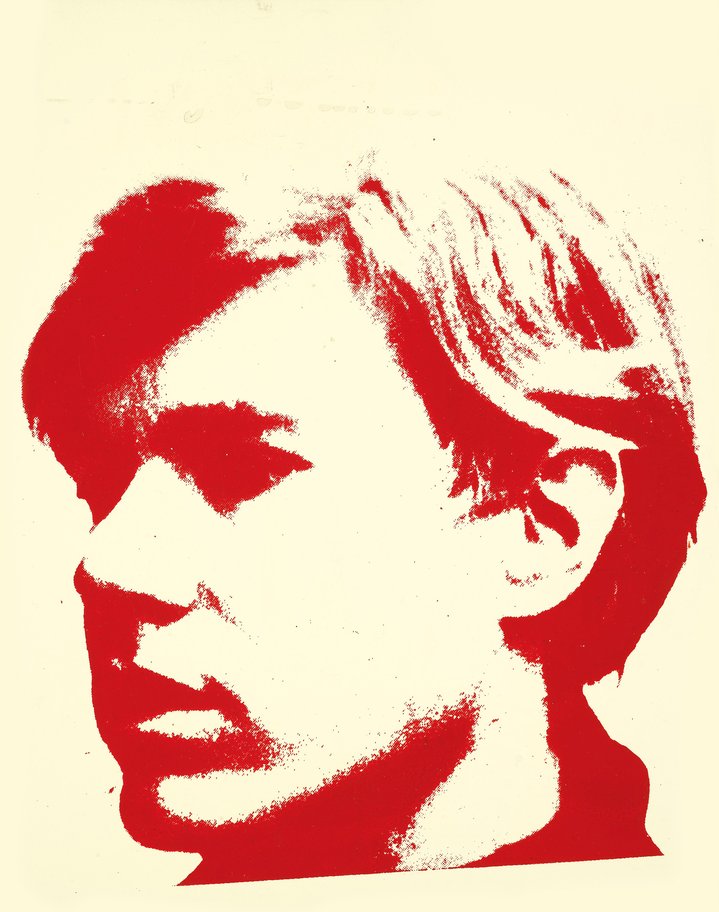

Nationalities don’t matter to Dolgicer when it comes to collecting. His favourite artist is American Ed Ruscha (b.1937), which brings him to the subject of one particularly treasured part of his collection, works on paper by Non-Conformist artists Ilya Kabakov (b.1933), Erik Bulatov (b.1933) and Oleg Vassiliev (1931–2013).

“Bulatov also uses text, something to which I have always been drawn. This is one of the reasons I began to collect Ed Ruscha, who is my favourite artist of the Pop Art era. I find Ruscha and Bulatov to be like opposite sides of the same coin in my collection,” Dolgicer explains.

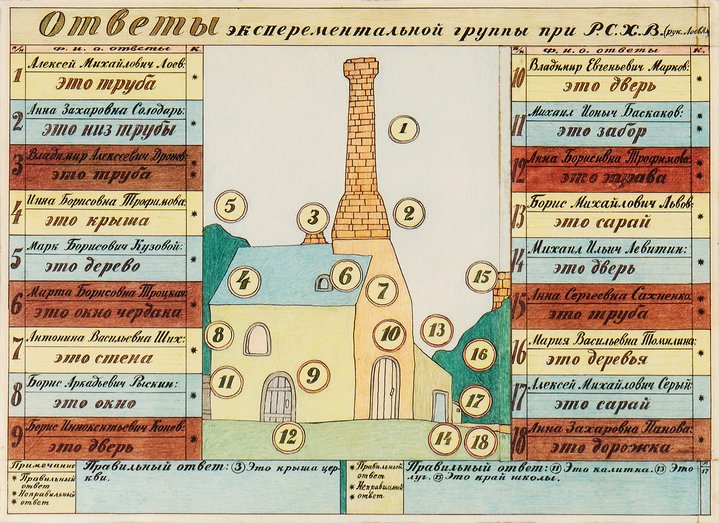

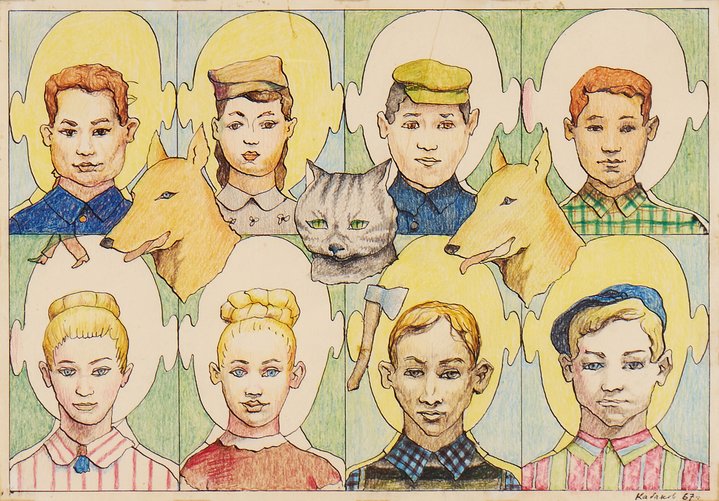

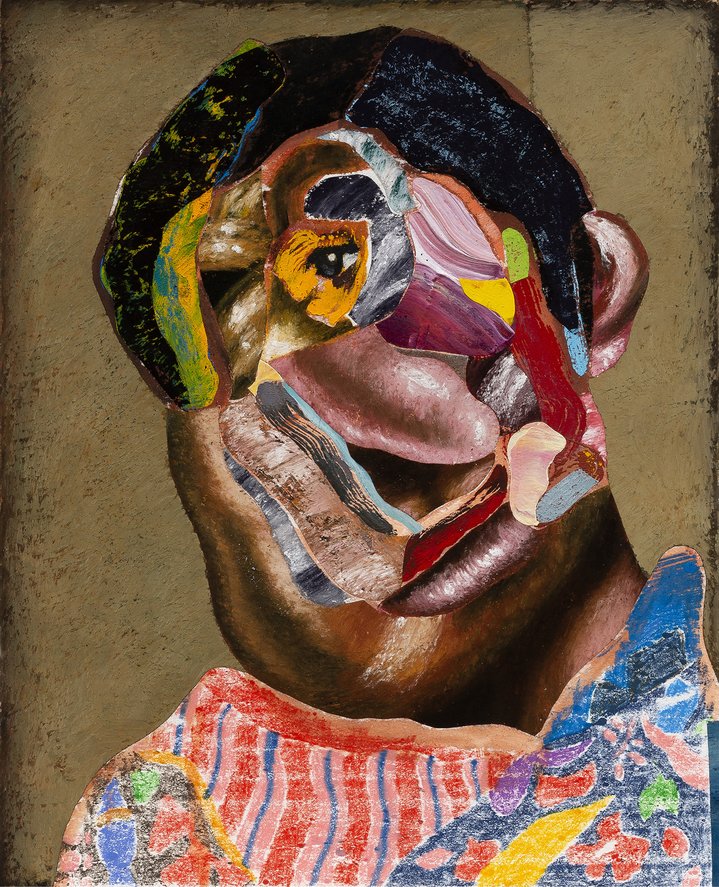

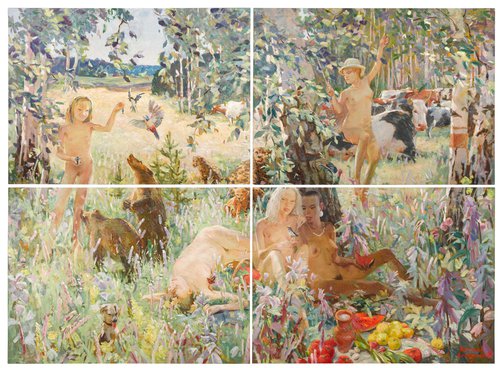

I ask him what drew him to these three artists in particular. “The answer is simple. When it comes to Russian Non-Conformist art, they are the best of the best.” He calls Kabakov’s drawings from the 1960s and 1970s ‘jewels’, however, it is for their conceptual quality that he reserves his greatest appreciation: “Kabakov provides a rich insight into the evolution of Russian art history. The range of materialism in Kabakov’s paintings extends into the conceptual realm in a way that only Malevich had achieved and, both those artists really pushed Russian art forwards.” His tastes as a collector are broad, and he is fond of photo-realist works, which accounts for his particular fascination with Oleg Vassiliev.

Asked about the commercial side of the art world, Dolgicer replies: “I view myself first as a collector and then as an investor. To reconcile both is very difficult, especially when it comes to blue-chip artists, who are very expensive. First, I would not buy an artwork unless the work itself really resonates with me and I would receive joy from having it on my wall. Secondly, I established a monetary threshold, which I only exceed if, in my view, it’s a good investment.”

Asked about the digitisation of the art market, as a collector and IT expert, Dolgicer points out that “art is one of the last luxury goods to trade online, and it has been very slow in going digital, but it is happening now and Covid-19 has undoubtedly accelerated the shift into e-commerce”. He sees it as a boon for many sectors of the art market, particularly for smaller galleries. “By growing their online presence, these galleries have more freedom to create and communicate an artistic narrative for their artists and exhibitions across the internet,” is his upbeat conclusion.