Maria Arendt: a stitch in time

The Russian artist known for inventive embroideries with a conceptual twist is staging a retrospective at the Moscow Museum of Modern Art.

Some artists treat their own works as something sacred, others don’t. Maria Arendt (b. 1968) falls into the second category. Stuck in London during the coronavirus lockdown, she and her sister, London-based artist Natalia Arendt, washed several of their textile creations in the Thames and hung them to dry among the birches in front of Tate Modern.

Maria Arendt comes from a prolific family of artists. Her grandmother Ariadna Arendt (1906–1997) and her grandfather Meer Eisenshtadt (1895–1961) were sculptors. One of Maria’s distant ancestors was a pioneer of Russian aviation, another one was the doctor who treated the poet Alexander Pushkin during his last days after he was shot in a duel in 1837. All this might sound superfluous, but genealogy is the key that uncovers all the hidden meanings and layers of Maria Arendt’s work.

“The previous generations of my family had produced so many heavy, massive objects. That’s why I have always felt that my own art had to be very light, almost immaterial. As if I had no moral right to fill more space with bulky stuff,” the artist confessed to me once.

So now her art is indeed lightweight in its mass, but not in its message. About 10 years ago, Arendt chose embroidery as her medium of choice. Moscow’s Kalinin School for Art and Craft (which has since changed its name to ‘Stroganov College for Design and Decorative art’), is where she studied folk crafts. Her decision was an instance of serendipity, prompted by necessity. Arendt was working at the time on her solo exhibition at Ruina (The Ruin), an annex of the Moscow Museum of Architecture. An atmospheric, although then derelict building, with crumbling wooden floors, elegant cast-iron stairs and red brick walls, it looked like an immersive installation in itself.

“I had planned to exhibit a series of drawings made on small clay tiles. Yet, at some point, I realized that they would be completely lost in that space. I needed something bigger and more visible,” the artist recalls. In despair, she came up with the idea of switching to embroidery. Indeed, big stretches of black fabric with outlines of everyday objects became her victory banners.

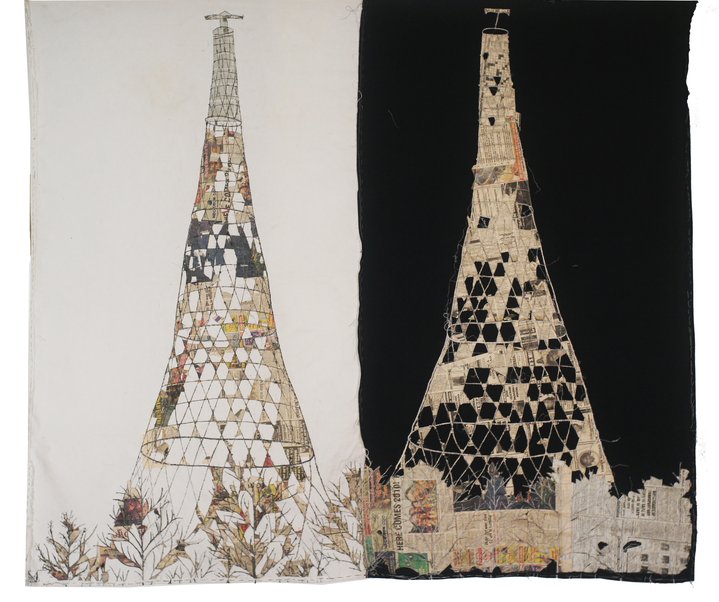

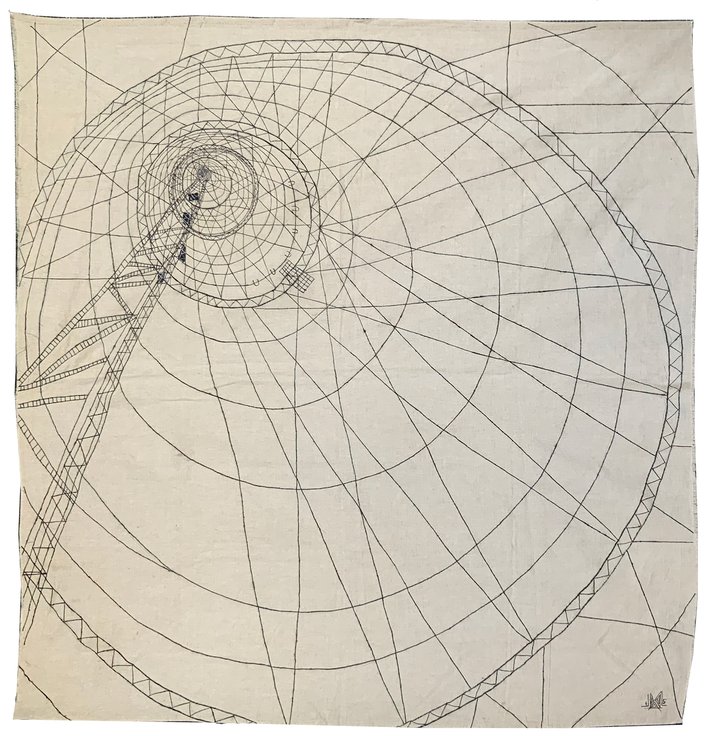

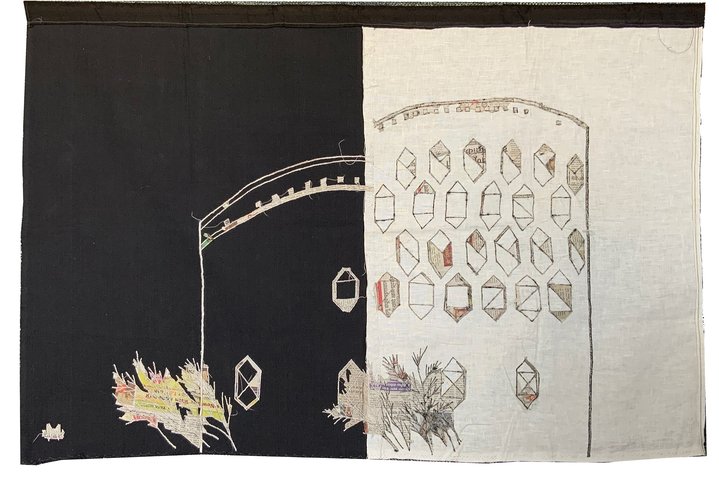

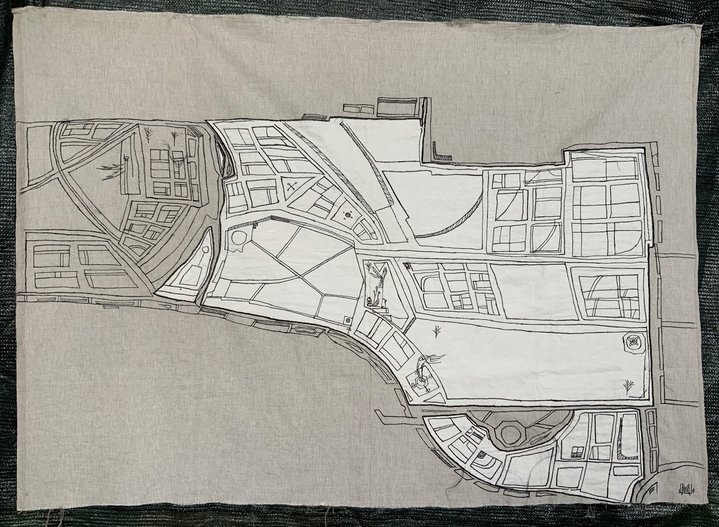

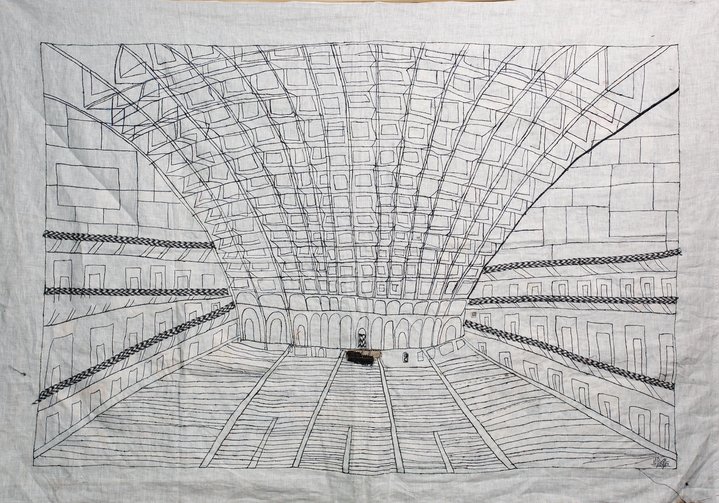

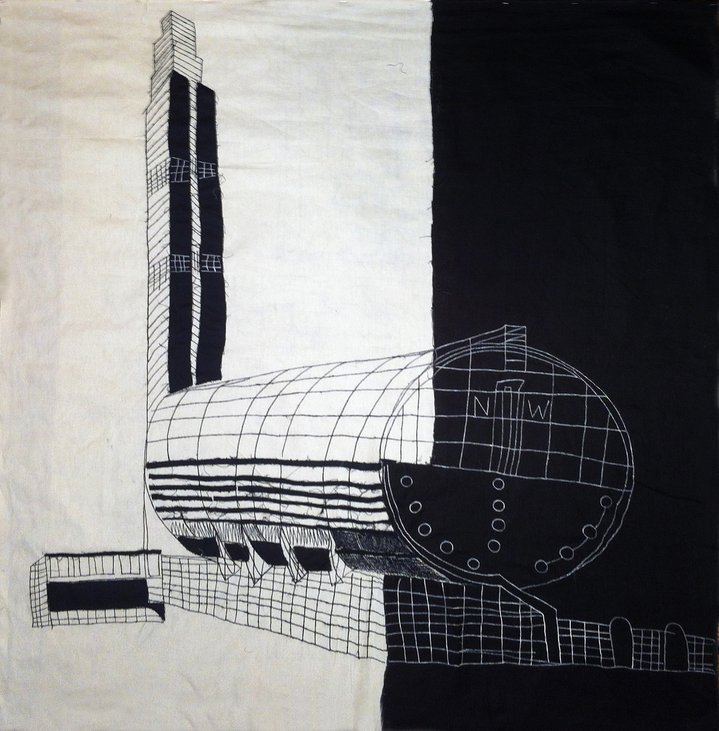

Arendt brought the visual vocabulary of contemporary art into an age-old craft. She cherishes the aesthetics of the rough and the unfinished, the spontaneity and the hanging threads. Her works have a curious effect of estrangement: there is a striking contrast between the medium and the message, the softness of fabric and the gravity of stone. Many of her works are dedicated to architecture, including the dome of Venice’s San Marco, the masterpieces of Russian Constructivism or Tel-Aviv’s Bauhaus architecture. They will play a leading part in her forthcoming exhibition, named ‘Architextile or All Sewn Up’. Arendt is fascinated by the unexpected fragility of endangered buildings. The Shukhov radio tower in Moscow, a 1920s monument under threat of demolition, became a recurring motive in her work. Another endangered structure, an old gasometer in London, which she stared at for months from a window of her sister’s apartment, inspired her most recent works: an embroidery and a video.

Arendt’s creations have an intriguing ambiguity about them. They can be viewed from any side. The reverse, patchy and uncouth, is dotted by scraps of old newspapers. This combination is obviously not Arendt’s own invention. Old newspapers are used as padding by embroiderers all over the world for purely technical reasons. Yet it took an artist’s eye to see their unpolished beauty. For her various projects, Arendt procures newspapers from different countries, printed in many alphabets, from hindu to hebrew. Thus, her works acquire a new dimension, as collage. At her shows, she prefers to hang them across the room so that both sides can be visible.

Her exhibition at the Moscow Museum of Modern Art spreads over two floors and contains five of Arendt’s projects made in the course of past 10 years. In the last room, there is a structure resembling a bedouin tent made out of her works and various textile objects from her home. There are layers and layers of them, one on top of another. “I am like a caddisfly, a creature that makes its habitat out of rubbish and debris and carries it around. My works and all these fabrics reflect different layers of my life. I carry them around, stitch them together and try to build something. Then it falls apart and I start all over again.” If you have ever dreamt of “entering an artist’s mind”, this is a the chance not to be missed. That’s how her medium works. In order to experience it fully, you should let her art envelop your mind and your body. And let it touch you, literally.

Maria Arendt. Architextile or All Sewn Up

Moscow, Russia

October 2 – November 1, 2020