Ekaterina Muromtseva: aiming high all the way to the sky

Unabashed by the lockdown, young Russian artist Ekaterina Muromtseva has turned her balcony into a gallery, where she stages exhibitions that only birds can see.

For Moscow artist Ekaterina Muromtseva (b.1990) her stay at the WHW Academy, an artist residency in Zagreb, turned out far more exciting than she could have possibly expected. It included a real earthquake and a two-month quarantine. The former destroyed a lot of buildings around the city and adorned the artist’s temporary home with a new crack in the ceiling. The latter deprived her latest project of its audience. An exhibition of her new works was already mounted in March, yet the public never had a chance to see it, as the lockdown was announced in Croatia on what should have been the opening day. Unabashed, Muromtseva came up with a new project called ‘Balcony Gallery’. She started to exhibit her works, mostly large watercolours, on her balcony’s railings. “Birds, stray dogs and occasional passers-by are now my audience,” the artist told me during a recent Skype interview. Earlier that day, she put up an exhibition aimed at birds, whose songs now rang strangely loud and clear over the deserted streets of the once noisy city. “I can hear them well now that trams and cars have stopped,” Muromtseva explains. “Their voices make me feel good, so I decided to do something good for them as well. I made their portraits and put them out for them to admire.”

The transition to online-only mode of interaction with the world proved testing for the artist. “Most of my projects are focused on people, so communication is an important part of my work,” she says. “Online communication is very different, I am not yet used to it. So now I am working for birds.” Her calm philosophical reaction to the global apocalypse is no surprise, given her background. Muromtseva studied philosophy at Moscow State University. As a student, she had happened to read Marcel Proust’s ‘In Search of Lost Time’, which had an immense impact on her. “I did not take drawing lessons as a child and used to think that you cannot become an artist, unless you are trained for it from an early age. But when you live through these seven volumes in which the protagonist gradually discovers a writer in himself, you too realize that you can create.”

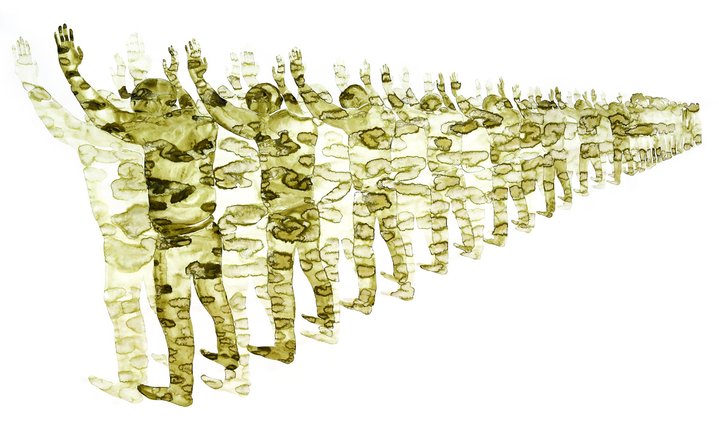

Muromtseva began to take lessons in academic painting and later entered Moscow’s Rodchenko School of Photography and Multimedia. Yet her preferred medium is surprisingly low-tech. In essence, it’s painting without painting. Her enormous watercolours with floating, semi-transparent splashes of paint are created without a brush. Muromtseva stretches huge sheets of paper on the floor, outlines figures with a pencil, pours large amounts of water on them and adds watercolour paint. When the water dries, an unusual iridescent effect appears. She invented this technique, by pure accident. “I had poured water over a big sheet of paper, added some watercolour and fell asleep,” she recalls. “I like the unpredictability of it: it is a work of nature, as well as my own.”

Muromtseva uses this medium, albeit fluid and capricious, to address poignant issues of history, politics, and collective memory. “I am trying to capture an individual’s presence in time,” she explains, pensively. “It’s trying to feel `big’ history in small personal stories.” Her solo exhibition ‘More than us’ staged at Moscow’s XL gallery in 2017, was inspired by the protest rallies in the city which were brutally dispersed by police. The large-scale watercolours reflected the pervading “aggressive power of the state”. “It’s difficult to stay away, when you live in Moscow and see its public spaces that should belong to us all, being forcefully taken over by the someone else,” the artist says.

Her recent series ‘Picket’, showing figures of protesters picketing with blank signs, was a tribute to the scandalous Ivan Golunov case. Golunov, a Russian journalist known for his investigative reports on corruption, was arrested in June 2019 “for possession and attempted sale of street drugs”. The substance in question turned out to have been surreptitiously put into his backpack by the very policemen who arrested him, causing a major public outrage. The first work in this series was initially conceived as a protest banner, Muromtseva explains. “I wanted to bring it with me to a rally in Golunov’s support and then decided to turn it into a symbol of solidarity, of a common cause that united a lot of people.” In September 2019, ‘Picket’ became a part of ‘What happens to others’, the artist’s first big solo show at the Moscow Museum of Modern Art.

The “big” and “small” histories intertwine in curiously unexpected ways in Muromtseva’s video works and multi-media installations. In her video ‘In this country’ (2017), the narrative is composed of fragments of essays about life in USSR written by todays’ Russian schoolboys and girls. The artist illustrated this bewildering assortment of misconceptions, clichés and unnervingly tragic maxims using an inventive shadow play sequence. “The historical narrative is monopolized by the state, by professors and other people who have some sort of license to write history,” she notes. “I wanted to find a different way to talk about it, to give a voice to those who are normally not allowed to speak.”

Her most valued audiences are fellow philosophers and elderly people from state-run retirement homes, which Muromtseva regularly visits as a volunteer. While working on one of her projects, she needed to talk with people of an older generation about their experiences. These research visits led to friendly discussions about art and even common drawing sessions. Elderly residents made their own homages to non-conformist heavyweights such as Ilya Kabakov (b. 1933) and Erik Bulatov (b. 1933), or painted rugs on the walls to give the bleak interiors a more “homelike” feel. (Rugs, expensive and difficult to come by in USSR, were used as wall decoration in many Soviet flats.) These friendly exchanges are of crucial importance for Muromtseva. “It makes me think that art is not some kind of a restricted area, reserved for a certain narrow circle of people. It can and should be discussed with wider audiences, with totally different people.” And, as it turns out, even with birds.

Ekaterina Muromtseva’s official website