Andrey Filippov at the Department of Eagles exhibition in Ekaterina Cultural Foundation, 2015. Photo Natasha Polskaya

Andrey Filippov: A Life in Art that ended way too soon

Moscow conceptual artist Andrey Filippov (1959–2022) passed away in July of this year. Gallerist and curator Elena Kuprina-Lyakhovich who worked with him for nearly three decades shares with us her personal tribute to the late artist.

We met in 1995 as I was just starting out in the cultural life of Moscow, and Andrey was an accomplished artist who had already achieved a lot, from his participation in the now legendary APTART Gallery exhibitions in the early 1980s, to major international exhibition projects and biennales. I was invited to coordinate an art project he and artist Nikita Alekseev (1953–2021) were overseeing at the Bakhchisarai Palace Museum in the Crimea. It was an exhibition of watercolours called ‘Dry Water’ by artists of the Moscow conceptual school and it was a very fortunate entrée for me into the art world as I quickly found this school to be incredibly exciting. This was not only an outreach project on a large scale - there were more than 30 artists taking part — it taught me a lot about how to communicate in the art world. Andrey gave me my first lessons about artists, about their work, their moods and ideas. He had that all too rare quality of someone who enjoyed the success of others, who tried to understand the perspectives of those who did not share his own views. He always had time and a natural affection for other people, he was a gentle soul; everyone referred to him as Andriusha.

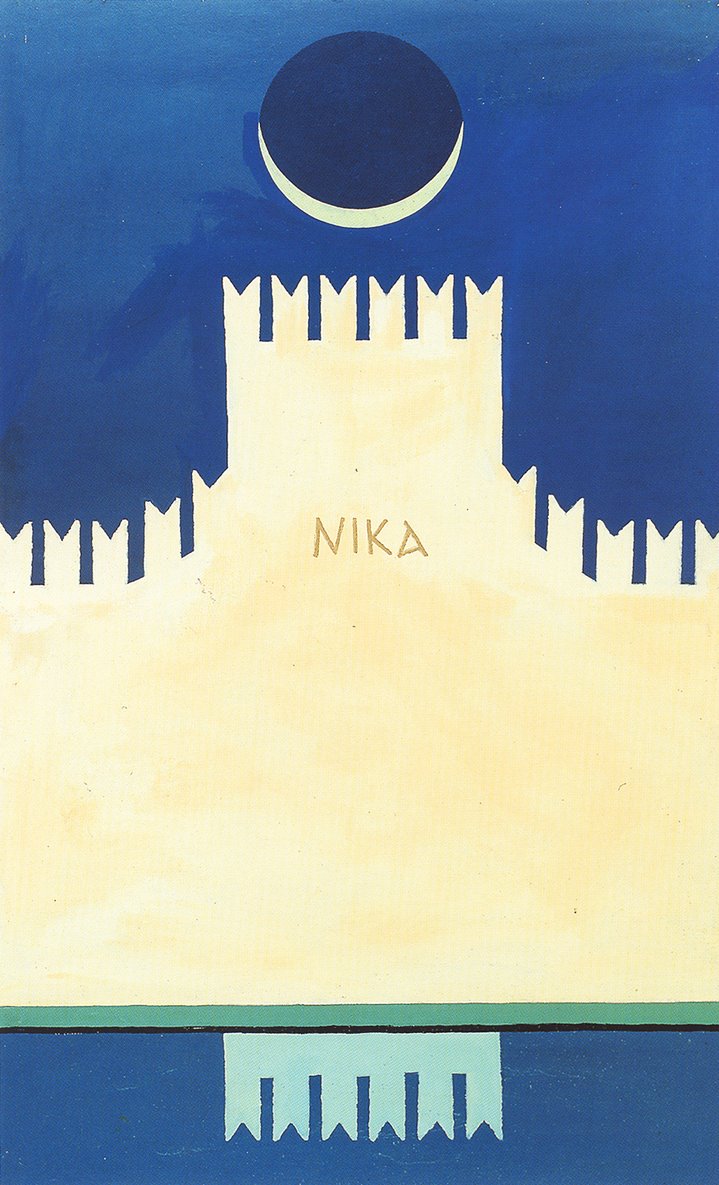

Perhaps it somewhat surprised me that despite his very soft, quiet nature, Filippov conceived and produced large international art projects, dedicated to geo-politics and the problems of being and of the spirit and of humankind in our complicated world. He had this way of looking at all of us from a very high-minded perspective, embracing centuries of history and fitting it organically into his work. A long-time admirer of the Byzantine Empire, Andrey believed its structures were in tune with humanity, and saw Constantinople as a 'heavenly city' prototype. Setting out for the viewer a long contemplative and philosophical approach, his works provoke the viewer to reflect on historical destiny, past and future, mythology and reality. Andrey saw the relationship between artist and viewer as an important dialogue where, in his words, "the artist thinks in images and the viewer in feelings and reflections. If they coincide, it turns out to be interesting".

Born in 1959 in Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky, Andrey Filippov’s father was a sea captain. At a very early age he was taken to Moscow, where after high school he entered the Moscow Art Theatre School of Stage Production. He first became known in the Moscow underground in 1983 for a work called ‘Rome to Rome!’ a kind of ‘artistic dedication’ he made during the exhibition ‘APTART in Nature’. This was a work by as yet an unknown artist and was noticed and praised by Andrei Monastyrski (b. 1949). Here's how Andriyusha liked to recall it:

"Monastyrski came up to me:

Whose work is this?

Mine.

It's brilliant.

He handed me the lyre".

Andrey later stressed something to do with his acquaintance with the Collective Action group practices, which produced a large number of good artists: "And this is by no means strange. What is usually considered a deviation is simply, as in nautical navigation, the deviation of the compass needle, that is, the angular difference between the magnetic and true north. In this gap, in fact, there is real art."

After this successful debut, Andrey became actively involved in the life of the Moscow conceptual circle, not only as an artist, but also as the initiator and organizer of many exhibitions. He was one of the founder members of CLAVA, the Club of Avant-garde Artists, a community of artists whose exhibition space was a hall in Peresvetov Lane.

In 1989, for the exhibition ‘Mosca-Terza Roma’, Filippov created ‘The Last Supper’, an emblematic installation that has since acquired status as a symbol of independent art from the USSR. On the most obvious level it seemed to be a (timely) funeral feast for the Soviet Union, but in reality it is about the Last Supper, which takes place during the liturgy. "If the artist were an icon painter, he would have made an icon according to the traditional canon, if he were a Renaissance artist, he would have made a fresco like Leonardo. But the artist makes a work in which, as through a cloudy glass, he tries to discern the Eternal Sacrament reflected in our souls."

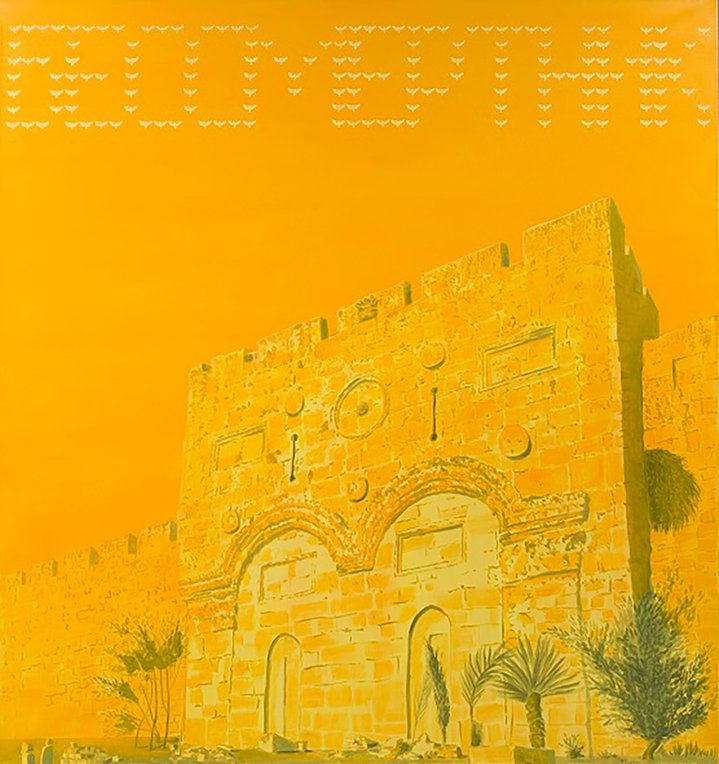

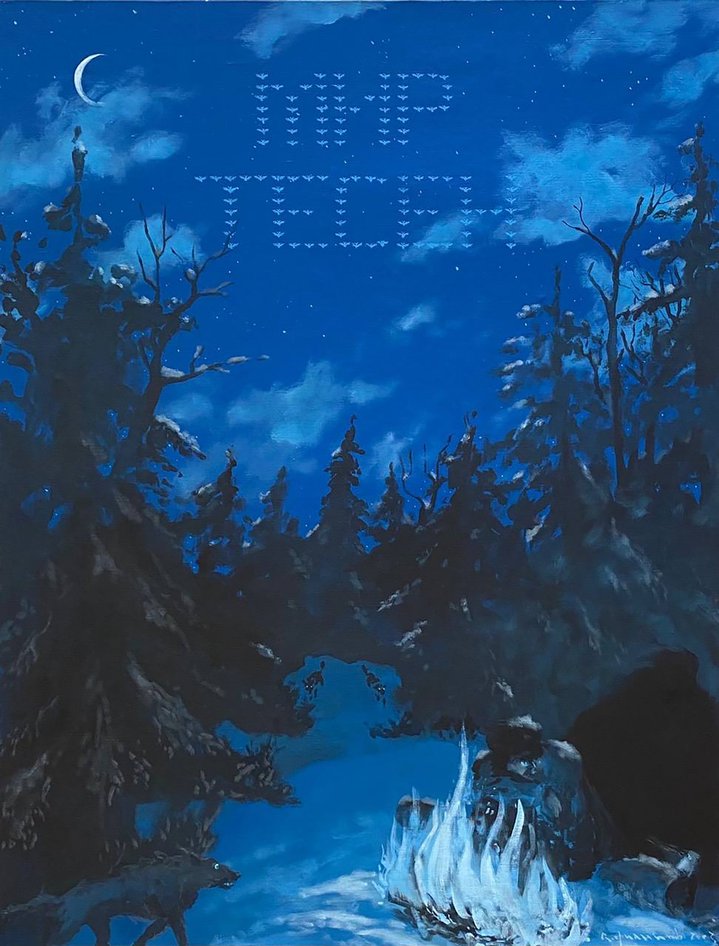

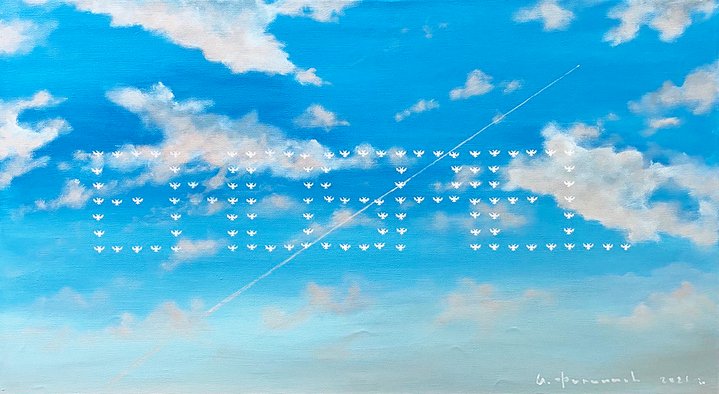

One of the most recognisable symbols in Andrey Filippov's work is ‘pixelated’ text in the form of double-headed eagles, which appeared on his canvases during the Soviet times, even before Perestroika. The artist later recalled: "I didn't know what pixels were, there was no such computer language back then. I just used eagles to write texts. That's my language. It is very important for me to work with a text, with an image, this is very much in the tradition of Moscow conceptualism and the Russian tradition in general, and icon painting: the word complements the image, the image complements the word, revealing mutual meanings." In Andrey's works, eagles are woven into inscriptions in different languages, forming spirals, flying up and soaring into the sky, as if making a declaration about what is happening down below.

Another important symbol in Andrey’s work: the battlements of a fortress, or 'swallow tails'. His monumental sculpture ‘Saw’ created in 2006 still stands in Thessaloniki, a project he had conceived on two occasions, at the turn of both the 1980s and 1990s. I like how art historian Ekaterina Degot wrote about this work: ‘A huge saw which cuts into the surface of the earth from underneath is the image of inexorable Fate that wounds mankind, like geological rifts. Only this fate strikes not from above, from where one expects it, but from the deepest depths, from where you find 'roots', a dangerous notion that leads to political earthquakes’.

In 2015, Andrey won the Kandinsky Prize in the 'Project of the Year' category. He did not expect it at all: "Winning the Kandinsky Prize shocked me. I had absolutely no idea I would receive it, especially because there was a controversial work ‘With a Wheel in my Head’ with a fez and a map of the Crimea on display at the exhibition. I thought ‘They won't give it to me.' But they did! In that sense, the cultural community is good."

Andrey’s all too early passing is a huge loss not just for his friends but for the Russian visual arts in general. Artists need to live long because often society and the general public only begins to understand their work once they are into their sixties and seventies and also because at the age of maturity, artists create works which generalize lived experience. They create with a sense of wisdom and acceptance of the world. I am very sorry that we will not see this ‘late period’ of Filippov's works, but that's how it is. It seems fate has told us it is almost impossible for someone to become even more wise and kind than our great friend and colleague Andriusha was, when he was alive.