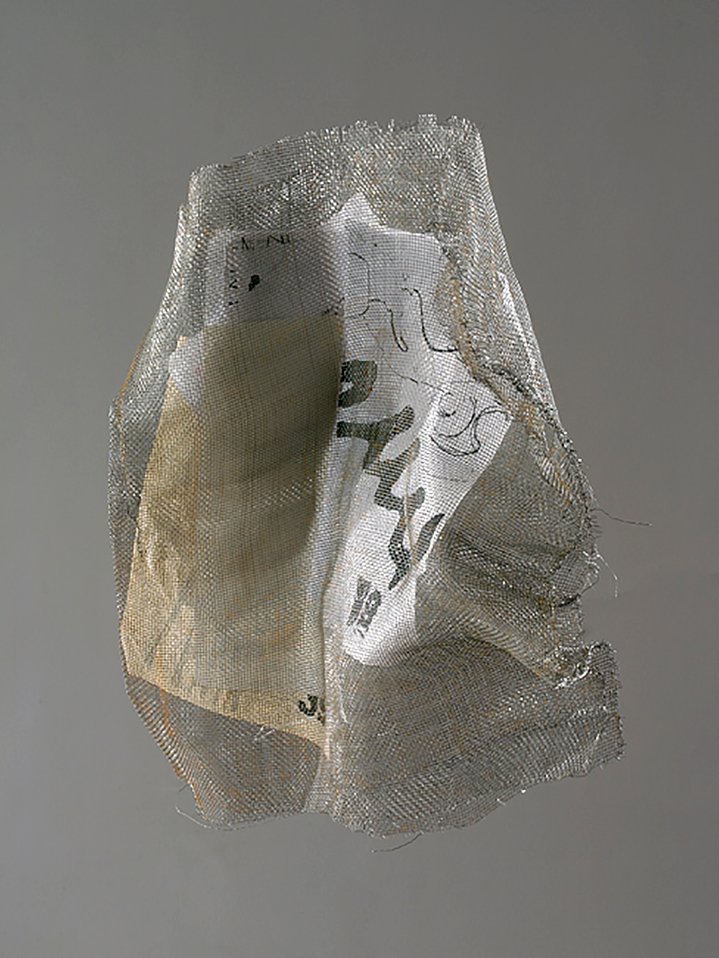

Andrei Krasulin. Portrait, 1978. Brass. 27x19x4.6 cm. Courtesy pop/off/art gallery

Andrei Krasulin: life in matter

The veteran Non-Conformist sculptor and painter who never throws away a piece of wood is launching a series of solo exhibitions in Moscow.

Were it a kinder world, art history may have learned about Andrei Krasulin sooner. Born in 1934, he studied monumental and decorative sculpture at the Moscow Higher School of Industrial Art. Although Krasulin came of age aesthetically in the Soviet Union during the more liberal 1960s, his first solo show only opened only in 1995 in the Lithuanian capital of Vilnius.

Following an initial first wave of exhibitions in early 2000s, Moscow institutions now seem once again to be making up for lost time. ‘Things Are More Pleasant’, on view until 26 February at the private pop/off/art gallery, is the first of three upcoming opportunities to view Krasulin’s recent work. Solo exhibitions at the State Tretyakov Gallery and the Moscow Museum of Modern Art are also planned during the next year and a half.

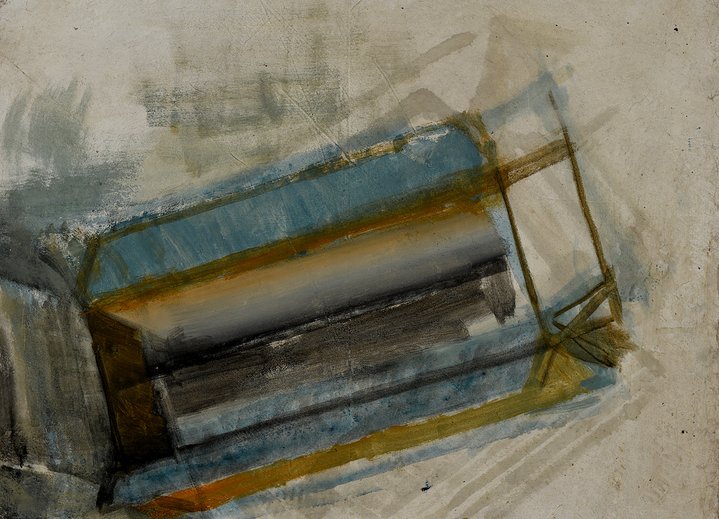

‘Things Are More Pleasant’ demonstrates Krasulin’s continued ability to parse the flotsam and jetsam of everyday life and to assemble new images using found objects or leftover materials in ways that express volume while also challenging our sense of gravity. The exhibition revolves around a cycle of paintings created during the last two years, in which Krasulin dissects the form of the box—a leitmotif in his sculptural and painting practice for several years. In abstracting the object, he asks viewers to contemplate qualities such as materiality and surface facture. The second section of the exhibition will feature new and largely monochromatic paintings that explore the relationship between figure and ground.

Krasulin’s body of work does not fit neatly into the standard period of Soviet art after World War II. His work does not obviously satirize Socialist Realism, as the Sots-Art movement did. Nor does it press narrative structure in the manner of the Moscow Conceptualists. What Krasulin does share with his contemporaries, however, is the desire to reinvestigate the language of modernism: rather than depicting what he sees, Krasulin manipulates materials and colours to transform our perception of the material properties themselves.

Perhaps because Krasulin often makes the visual and tactile properties of materials the subject of his work, there is a great deal of fascination among art critics with his process of selecting materials. In his 1998 essay ‘Subject, Matter and Space’, late art historian Dmitri Sarabianov wrote that in Krasulin’s assemblages of husky wooden blocks and metal brackets “the meaning is largely explained by their material… they may resemble the shape of a cathedral or an architectural façade,” although they are “not meant to imitate specific objects… the constructions should be considered evidence of life in matter, life that has found refuge in something or another.”

Krasulin’s particular ability to sense and infuse life into all varieties of matter becomes clear when visiting his studio on the edge of Moscow’s Sokolniki Park. Seemingly every surface of the space – at times also the floors and ceilings – are occupied with works in progress. Little seems ever to be thrown out. Wood shavings, heavy beams, canvasses, papers, sketches and stretchers, the books he has read, photographs of projects, loose notes, ephemera like the spare change one finds in an old coat pocket: such details are captivating in themselves.

I asked if he ever cleans up the studio, and if so, what that looks like. “Cleaningthe workshop is a very important creative process,” he explained. “It changes my perspective on everything, it opens it. Once, I swept the workshop and realized that what was rubbish turns into harmonic rows, into a jewel. With each movement, new constructions arise on their own. This is excellent evidence that there are no accidents, we are dealing with a change in patterns.”

Leftovers are never post-life. His studio is not simply a space in which he comes to create; the studio itself and its contents are primary sources of past projects, andpotentially new ones. By reusing discarded materials or recycling bits of other works, Krasulin is constantly self-referencing.

He turned this relationship into both source material and finished object, explicit in his 1994 sculpture ‘Archive’. The artist haphazardly pinned shredded scraps of paper to the top of a metre-and-a-half-long iron tube, suggesting that these materials, in their non-chronological accumulation and presence, nonetheless possess an implicit value.

Perhaps the quintessential example of Krasulin’s ability to both create and repurpose an archive is a ladder-like sculpture he made in 1997 from 500-year-old wooden beams, taken from the house of German painter Lucas Cranach the Younger (1515–1586). The beams had already been removed from Cranach’s historic house during a restoration project; Krasulin happened upon them during an artist’s residency in Germany that year and conceived a sculpture project in Cranach’s house.

Krasulin indexes himself to his art objects in ways other than remnants from prior projects. The lacquered wooden wall panel Krasulin created for the foyer of Moscow’s International Music Center in 2002 is one of his few works that does not bear his physical inprint. “It is now completely out of fashion to evoke human craft in contemporary art,” he lamented.

Nonetheless, the artist often leaves evidence of his presence in the objects he makes. Sometimes this even takes the form of smudges of dirt or a partial footprint. When I viewed some of his works on paper, many were stacked on the floor. This did not make sense until something Krasulin said later: “I don’t intentionally age any of my materials. But I don’t like pure white paper. I’m afraid of it. It should lie on the floor until I need it, be walked all over.”

If the act of synthesizing an idea into a material form seems to be second nature to Krasulin, it is not easily explained, not even by the artist himself. My question about the reasons behind his choice of materials for the current exhibition was met with a blank stare: “I cannot answer questions that begin with why.” In other contexts, however, Krasulin has likened his artistic process to what the Chinese call “wuwei”. This translates roughly as “non-action”, the idea being that an artwork should develop naturally. Krasulin’s approach is the opposite of intentionality and formulated task. It reveals something about his approach to his studio space: leave it long enough, rifling through occasionally, and you will eventually unlock something. Given the wait time, I inquired how often he comes to work in the studio. “Every day?” “No,” he deadpanned: “Some days I don’t leave.”

Andrei Krasulin. Things Are More Pleasant

Moscow, Russia

22 January – 26 February 2020