Andrei Monastyrski: the mysterious guru of Moscow conceptualism

The founder of the legendary ‘Collective Actions’ art group is unveiling a new exhibition at Moscow’s XL Gallery. His autobiographical novel was also recently translated into English.

An exploration of the figure of Andrei Monastyrski (b. 1949) could have a multitude of starting points: a snowy field on the outskirts of Moscow where a group of young people are gathered in anticipation of an unknown event; popular outrage around last year’s purchase of his artwork by the State Tretyakov Gallery; his literary memoir of personally experiencing schizophrenia. My own first encounter with the iconic photograph of his action ‘Slogan’, which stuck in my memory; our daunting phone call a couple of days ago; or the fact that my father (with our family dog) took part in one of his actions a year before my birth. He is the favourite artist’s favourite artist, a whimsical eccentric, an obsessive hoarder of archival material; a madman, a writer and poet and an intimidating colossus of cerebral magnificence, so much so that one of Moscow’s foremost contemporary gallerists Elena Selina wrote an explanatory text for his 1996 exhibition titled ‘Why I am Afraid of Andrei Monastyrski’. Now, he is returning to her XL Gallery, with a forthcoming exhibition due to open in April, entitled ‘Atribut’ (“Attribute”). It will show twenty-five videos filmed from his apartment window from 1998 to the present, along with several objects. But what the real “event” in encountering this exhibition is likely to be is unpredictable, as Selina puts it: “He is always, with unflinching consistency, unexpected and new.”

Monastyrski’s name (he was actually born Andrei Sumnin, he took this pseudonym as a pen name while writing poetry as a child) is firmly entrenched in the canon of conceptual art. He is a founder and key proponent of Moscow Conceptualism, along with such names as Ilya Kabakov (b. 1933), Dmitry Prigov (1940–2007), Erik Bulatov (b. 1933), and Nikita Alexeev (1953–2021). His entry into art lay through literature: experimental poetry became visual poetry, then morphed into objects and performances. He says he began self-identifying as a conceptual artist in 1975, with a series called ‘Elementary Poetry’, to which his first two objects belong. In ‘Kucha’ (“a pile”), he asked visitors to donate unwanted small objects, be it a matchstick, a button or coin, and then piling them up on a specially designated podium. Every donation was supplied with a receipt and documented in a record book which signalled the beginning of a lasting leitmotif in Monastyrski’s oeuvre – the importance of documentation.

The second work, ‘Pushka’ (“Cannon”) involved a box out of which a long tube protruded; the viewer was invited to look inside and press a button, but instead of an expected visual stimulation he would hear the sound of a doorbell ringing, creating a kind of sensory dissonance or, as Monastyrski puts it, “causing a change of perception paradigm.” Both objects were presented in the artist’s apartment, so who was the intended audience? “Of course, it was for a very narrow circle, artists, poets, writers, musicians and so on. It was art for art’s sake...” the artist explains. “In the beginning, it was wider and gradually narrowed.”

This narrow circle of friends – at once, participants and the audience – crystallised in 1976 into the ‘Kollektyvnie Deystvia’ (Collective Actions Group). They sent invitations to select guests – at once, spectators and participants – to join them on their trips, usually to the suburban countryside outside Moscow, where they staged unpredictable happenings they called ‘actions’. According to the artist: “Everything that happens in such a situation can be divided into what happens in the empirical sphere (according to the initial plans of the organizers) and what happens in the mental sphere.”

In the first such action ‘Poyavlenie’ (“Appearance”) of 1976, thirty invited participants gathered in a field on the outskirts of Moscow. They waited until eventually two figures appeared and walked towards them. Upon meeting the group, they handed each member a typewritten and signed receipt/certificate confirming their participation in the action. Subsequent analysis of this rather minimal event revealed that it implied the inversion of audience and spectator (who was it that “appeared” before whom?) and focused in on the anticipation and “zone of indistinguishability”, before understanding of the event takes place (as the figures approach but are not clearly seen), effectively teasing apart the levels of consciousness of perception and participation, on an almost mystical level.

Was this intention understood? Not by everyone. “An artist happened to be there who wasn’t of a conceptual inclination. When he saw what was happening [...] he started waving his hands about and shouting: ‘Charlatans! Crooks! let’s all leave!’ And this was a magnificent reaction that always accompanies something new in art.”

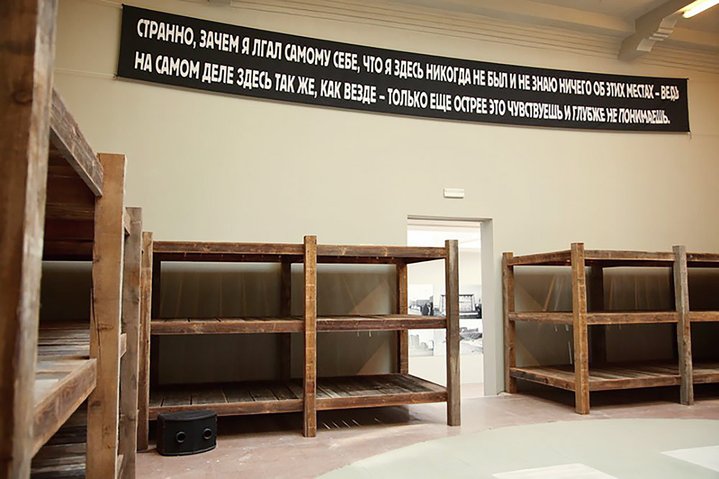

They continued creating regular events that contributed to this “aesthetic existential practice”. The second action ‘Lieblich’ (1976), invited audience members to a snowy field where an electric bell had preliminarily been buried and was ringing continuously. ‘Lozung’ (“Slogan”, 1977) was a huge red banner with white letters spelling out “I DO NOT COMPLAIN ABOUT ANYTHING AND I ALMOST LIKE IT HERE, ALTHOUGH I HAVE NEVER BEEN HERE BEFORE AND KNOW NOTHING ABOUT THIS PLACE” stretched between two trees in a deserted landscape. The image stuck with me, because it resonated with a bittersweet existential optimism and it was funny. ‘Balloon’ (1977) invited the participants to blow up numerous balloons and stuffing them into a huge balloon-shaped fabric, which also contained a ringing bell. This amorphous shape was then set to drift down the Klyazma River. By 1985, they were onto their fortieth action: ‘Vorot’ (“Winch”) involved turning a winch with lengths of fishing line attached to various faraway trees until they snapped, which would take up to an hour. Monastyrski recalls: “By the end of the action, the snow stopped, the fog cleared, the sun came out. The whole field was covered with snow. Thus, the meteorological side of the action corresponded to the score of ‘The Winch’ (the interaction of the forces of yang and yin, heaven and earth, darkness and light).”

Such analyses from the artist and other participants contribute to the so-called “factography” of Monastyrski’s personal archive fever: generating a huge web of interconnected and overlapping material. This documentation of 61 actions that took place up to 1998 was published in the now iconic five volumes of ‘Kollektivnye deistviya, Poezdki za gorod’ (“Collective Actions, Trips out of Town”). The actions still continue today, with a varying line-up, so, by now, the number of volumes has reached 14. So, could a familiarity with this material, then, in line with the logic of conceptual art, supplant physical attendance and participation of the audience? No, retorts Monastyrski: “It’s always the event: it includes space, field, snow, forest, sky, wind. [...] Spatial temporal experiences – that was the main thing in our actions, the idea was like a reason, an instruction, a concept. It was just an excuse in order to generate this feeling of eventfulness.”

This contributes to the differentiation of Monastyrski, Collective Actions and Moscow Conceptualism in general from conceptual art as it existed in the West, exemplified by such key proponents as Joseph Kosuth and Art & Language. Leading contemporary art theoretician and philosopher Boris Groys published an early essay called ‘Moscow Romantic Conceptualism’ in the Paris-based A-Ya magazine, which came to define this generation. In it, he admitted to the incongruity of the title and, yet, he knew no better term for the contemporary art movements in Moscow at the time.

“A characteristic common to all these works is their pure ‘lyricism’, or their dependence upon the viewer’s predisposition. [...] These indications pointing to the presence of magic forces can be regarded as facts of art opposed to facts of reality, that cannot be explained but only interpreted. [...] Western art says something about the world. [...] Russian art, from the age of icons to our time, seeks to speak of another world.” This schism between the objective reality and the subject’s solipsistic perceived universe, is explored and expanded in Monastyrski’s novel ‘Kashirskoe Shosse’. It states plainly at the outset that in 1982, he began to go insane and meticulously recorded the process in a diary. The “insanity” described here bears obvious resemblance to the experience of conceptual art, foregrounding philosophical questions of perception, objectivity, evaluation, temporality, as much in the reader as in the described subject. In wanting to distil and relate the iconographic space which he experienced he found it difficult to distance “himself from himself” as both subject and author and, as a result, he transformed the state into actions. The novel has been translated into English and will be released in May 2021 by the Moscow’s Garage Museum’s publishing department.

In 2003, Monastyrski was awarded the Andrey Bely prize for literature, in the category ‘Services to Literature’. And now, the novel is about to be published in English with illustrations by Pavel Pepperstein – a younger proponent of Moscow Conceptualism, himself a writer and artist, who considers Monastyrski a “constitutionally shamanic type” and his teacher. Existing for a long time in a cave of introspection, except for a narrow circle of like-minded friends and collaborators, recognition is catching up much later with this “guru”. Monastyrski was the Russian representative at the Venice biennale of 2011. With Groys in the role of curator re-framing Collective Actions in a contemporary global context: “Despite the fact that he began a long time ago, his practice was very current, or rather, even now is becoming more current than it was, that is the practice of participation, of creating events, situations that involve viewers and visitors. The involvement of the viewer into the artwork and the event of the artwork. Which is now the most current trend in contemporary art right now and he is a forerunner of this tendency.” Most recently, Monastyrski caused a stir with the work ‘Branch’ (1996) – a piece of board with four rolls of cellotape holding up a found tree branch, which is threaded through the middle. Monastyrski describes Branch as “an actionist ‘musical’ single-use object (instrument) to get the sound of unwinding scotchtape. However, it is conceived in such a way that this sound is only present as an opportunity.” Its purchase in 2020 by the State Tretyakov Gallery caused a media and public maelstrom.