Alexander Shishkin-Hokusai: a fantasy in plywood

Courtesy of the artist and the Russian Pavilion, Venice

Alexander Shishkin-Hokusai’s “Flemish School” installation will occupy the whole floor of the Russian pavilion at the Venice Biennale. While the artwork was being packed for shipping, he told Russian Art Focus what it’s all about.

Despite being about to represent Russia both at the Venice Biennale, which runs from May to November, and at the theatrical Prague Quadrennial in June, Alexander Shishkin is not used to being in the spotlight. He has quite literally worked for many years behind the scenes. Trained as a stage designer, he created sets for many theatres in St. Petersburg and Moscow. Shishkin, who was born in 1969 and graduated from St. Petersburg’s Institute of Theatre, Music and Cinema in 1995, collaborated with famous Russian stage directors such as Andrei Moguchy and Yuri Butusov, and is a four-time laureate of Russia’s most prestigious theatre award, the Golden Mask, in the “stage design” category. Yet he gradually realised that all this was not enough. “Theatre is basically a black box with no doors or windows. People who work on a show spend months locked up in this air-tight bunker, like in a submarine,” he once confessed to me. “I wanted to get out and breathe some fresh air.” The urge to create and experiment at leisure beyond the reach of the dictatorship of directors and looming deadlines was another, probably more serious reason for setting foot on the strange soil of contemporary art. The border between theatre and visual art is getting more and more blurred nowadays, yet Alexander prefers to separate his two creative identities. He invented a cartoon-like pseudonym, Shishkin-Hokusai, for his artistic practice. It is a pun which is quite transparent to his compatriots. Ivan Shishkin was a Russian classic, a 19th century landscape painter whose iconic depictions of nature were reproduced in Soviet primary-school textbooks. Living with such a last name is a challenge for any artist. “Shishkin’s name has become a brand. He’s like Andy Warhol in Russia,” Alexander explains. “Hokusai is a Japanese Shishkin, a brand that is no less stereotyped.” Shishkin admired the graphic style and aesthetics of the 19th-century Japanese artist, and was interested in starting a sort of spiritual collaboration with him. “Now part of his energy is working for me,” he believes.

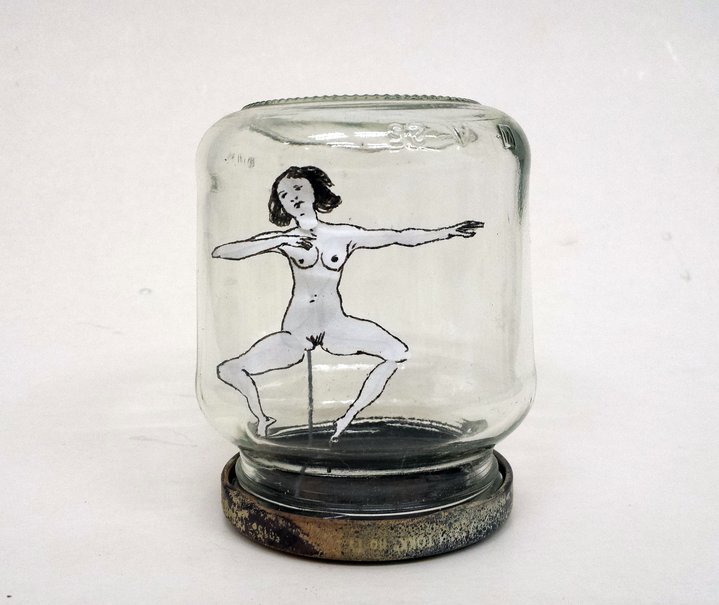

His first artworks stemmed from a stage-designer’s everyday working process. The cut-out paper characters from his early series “Russian Ballet” and “Juices of Light” are reminiscent of the paper human silhouettes which theatre designers use in scale models of their future sets. In Shishkin-Hokusai’s artworks, the set disappears but the staffage figures remain. They develop their own life and personality. The series “Juices! Light!” where witty mise-en-scènes played out by paper characters took place inside cardboard juice packs, made their way onto the long list for Russia’s prestigious Kandinsky Prize in 2011. Yet the artist's major breakthrough came when he switched from paper to plywood, another perishable, but less fragile material. That was the moment when his art finally came out into the open and eventually hit international art fairs. His installation “Storming,” dedicated to the Russian Revolution of 1917, was shown at the London Art Fair by the city’s Shtager gallery in January. Shishkin-Hokusai takes his creations out to the woods, plants them in the snow or moss, and arranges then rearranges them in different ways to create complex and absurd scenes of rallies, war or worship. The result seems to be a contradiction of terms: public art without any visible public. His only audience are wild animals or the occasional mushroom-picker. These short-lived compositions live on as photographs, which he plans to publish in book form one day.

Shishkin-Hokusai thinks spatially, as any theatre designer does, yet he is fascinated with two-dimensional figures. In essence, all of his work is about the adventures of 2D-characters in 3D-space. Runaway graphic art invades reality and punctuates its very fabric, a paradox that disturbs uninitiated viewers — sometimes to the point of moral outrage. During the Art-Prospekt street art festival in St. Petersburg, his “Sleeping Gardeners," installed in the yard of a residential building, was removed at the request of its inhabitants. They were shocked by the sight of nude plywood figurines, propped on their spades with their eyes closed. Somebody reported the “indecent” artwork to the authorities, who ordered told the artist to remove the offending figures at once. “I was surprised by this reaction to nudity,” the artist confessed. At the next year’s festival, he dressed his character in “vatniks,” shapeless cotton-padded jackets worn by Russian peasants, soldiers and prisoners as a sort of protest.

For him, the nudity of his characters has no erotic undertones. He believes that “clothes always signify a certain social role,” while in his mind, the naked body is associated with the biblical Garden of Eden, classical antiquity or Nature.

His biggest artwork to date, "The coming-of-age rituals,” unveiled in 2015 in the St. Petersburg's private Street Art Museum, consisted of 200 human figures, most of them naked, sitting on chairs and being lectured by another naked character who looked exactly the same but was much bigger in size: a caustic parody of all the institutions regarded as embodiments of power and knowledge.

“It does not matter who this person is,” Alexander says about the figure of the “teacher.” “Anybody can occupy this position, as soon as they are appointed to it. It’s only the labels that matter. Call yourself an artist and you’ll become one. Call yourself a director of something and you’ll become a director.” Ironically, the same irreverent attitude to institutions will, apparently, prevail in his installation at the Venice Biennale, the most institutionalised art event in the world. The whole Russian pavilion, with its upper floor occupied by a Rembrandt-themed work by film director Alexander Sokurov, will be dedicated to the Hermitage Museum.

Shishkin-Hokusai’s total installation, for which pavilion commissioner Semyon Mikhailovsky suggested the title “The Flemish school,” is focused on “the museum as an institution, a very special kind of space, the Hermitage itself being just a starting point for the game,” Shishkin-Hokusai explains.

At the same time, his work is inspired by his own personal relationship with the Hermitage: as any child born and raised in Leningrad/St. Petersburg, he was a regular there from an early age. For him, the gigantic museum is a separate world, a “Vatican of St. Petersburg, a haven, a sanctuary. [...] It is not necessary to have any background knowledge of the Hermitage in order to understand this artwork,” he says, “yet those who have visited the museum will recognise some of the exhibits.”

The masterpieces will, unsurprisingly, be recreated in plywood, his signature material. The installation will have moving elements, like some of his earlier works created for gallery shows. Shishkin-Hokusai, thanks to his theatre background, has always had a soft spot for old-school machinery. One of the important themes of the work is a conflict between the two functions of a museum: a stronghold of science as well as a place for entertainment. It is an ambiguity that every museum today, including the mighty Hermitage, can neither ignore not escape.