A vanished Soviet collection

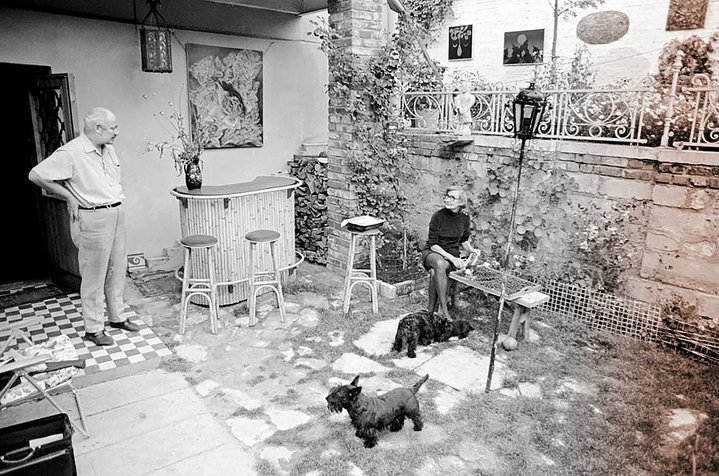

Nina Stevens, a very privileged Soviet collector, and her amazing house where diplomats, communist officials and underground artists mixed and mingled together.

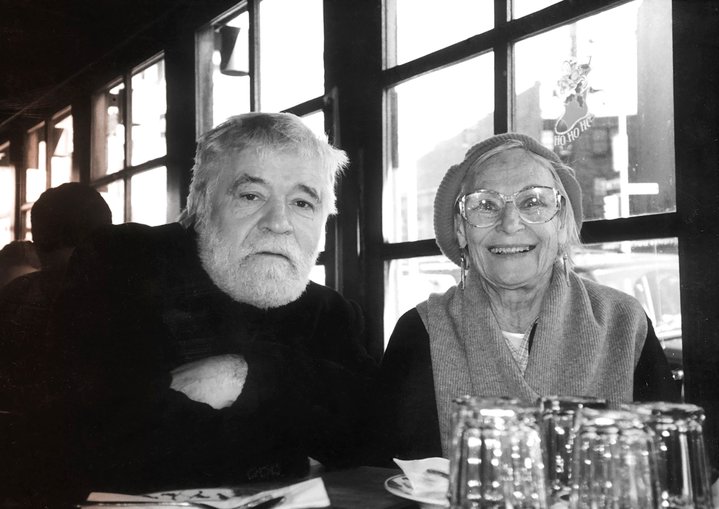

This is the story of Nina Stevens, a Soviet woman who married a dashing American journalist in the years of Stalin’s terror. By the 1970s, she was living in a style that no Soviet citizen could ever have dreamt of. Her husband, Edmund (always known as “Ed”) Stevens, had a fine taste for icons, while she eventually developed a passion for non-conformist art and acted as a fairy godmother to struggling artists.

Her husband managed the impossible in Soviet terms and somehow got hold of an exquisite 19th century Moscow mansion. That jewel, once built by architect Nikolai Faleyev for his own family, had earlier been the temporary home of John Reed (1887-1920), author of ‘10 Days that Shook the World’. Vladimir Lenin is supposed to have personally assigned the property to Reed after its confiscation following the 1917 Bolshevik revolution.

When Stevens obtained that elegant residence, it was in bad shape after years of neglect. He would later say that Soviet handymen employed at the U.S. embassy helped to restore it, while working for Stevens after hours. The family moved into the new home in the 1960s. Once established, the house turned into an irresistible magnet for diplomats, journalists and the Soviet intelligentsia.

The Stevens family enjoyed unbelievable privileges during the years of Stalin’s bloody reign. In 1939, the couple was given permission to travel to the United States. In those times, it was an un-heard of privilege for an ordinary citizen like Nina. Once there, she graduated from Boston University and the couple only returned to the Soviet Union after World War II had ended in 1945, but then left for Italy the next year and only came back several years after Stalin’s death in 1953.

Their house was a treasure trove, filled by Nina’s raids on antique shops, as well as private purchases. Very striking early Russian icons hung on the panelled walls of the huge kitchen in the basement, the real heart of the house and Ed’s favourite retreat. Upstairs was an elegant, but very formal drawing room filled with delicate furniture and other antiques.

It was clear from the drab way in which Nina dressed that fashion had never interested her. She was instead adventurous and nonconformist art became her passion.

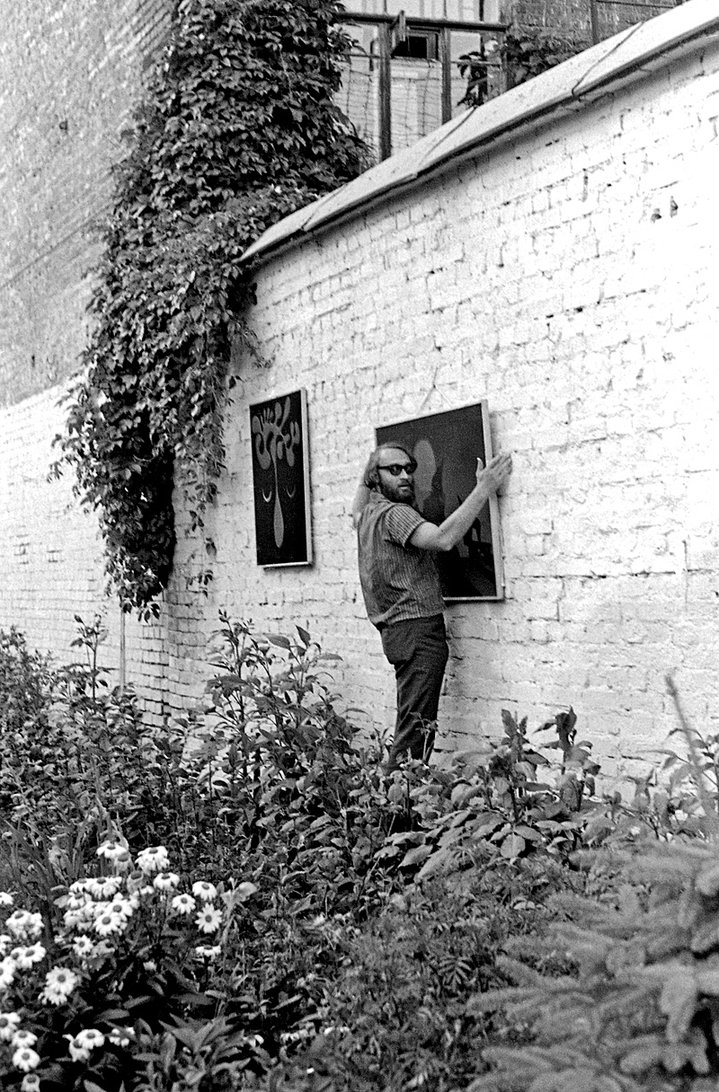

Artist Vladimir Nemukhin (1925-2016), who knew Nina well, described her as “a very grasping woman, not very well educated, who began to literally patronise ‘independent artists’ in the early 1960’s”. Despite that harsh judgement, Nemukhin would learn to see another side of Nina.

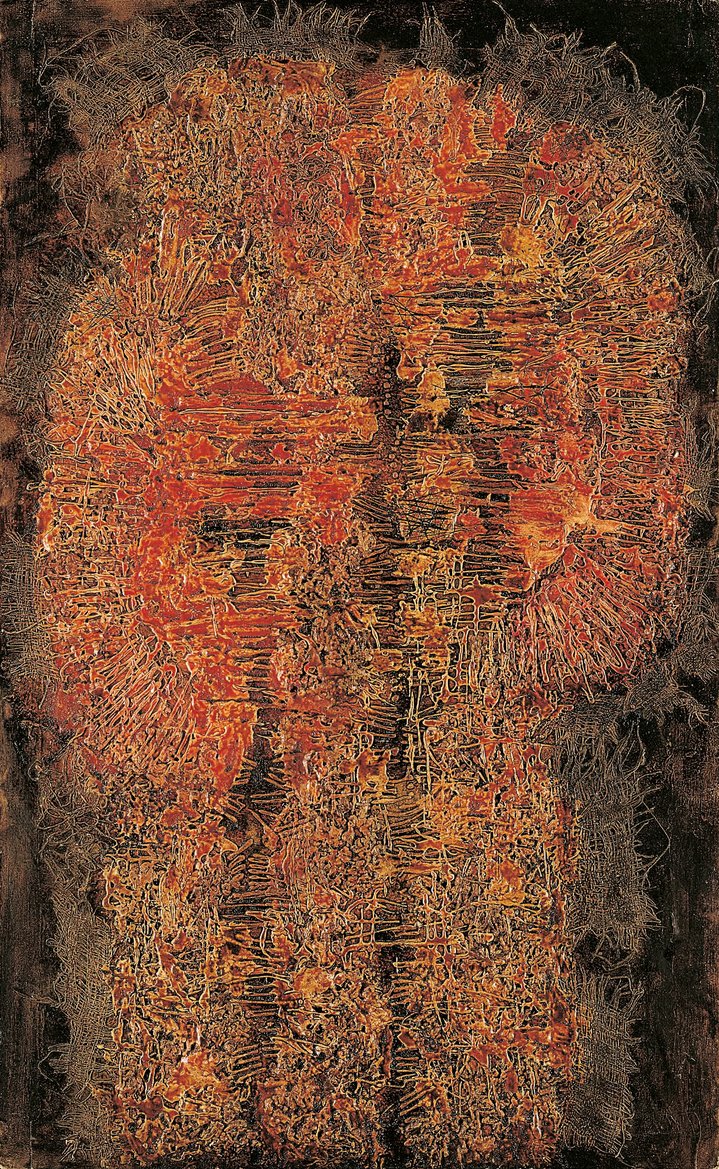

She may not have known much about art, but Nina had a great business sense. It was she who first brought the Soviet nonconformists on the international stage. As usual, she and her husband knew how to organise what was impossible for any other couple in the Soviet Union.

In 1967, Nina Stevens not only took her collection of nonconformist art to New York, but also managed to sell over 50 of those works to the great American collector Norton Dodge (1927–2011).

Predictably, Nina had earlier met that professor of economics in Moscow. Dodge has gone down in history as the single biggest collector of “dissident” Soviet art, having accumulated over 20,000 nonconformist works by the time he died.

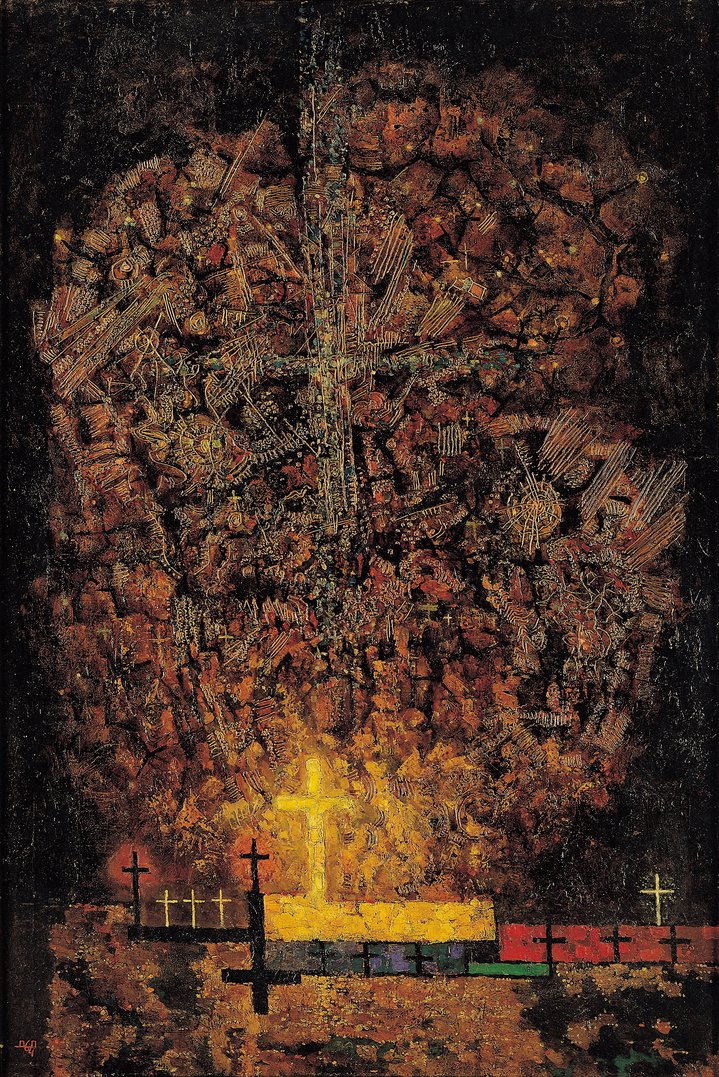

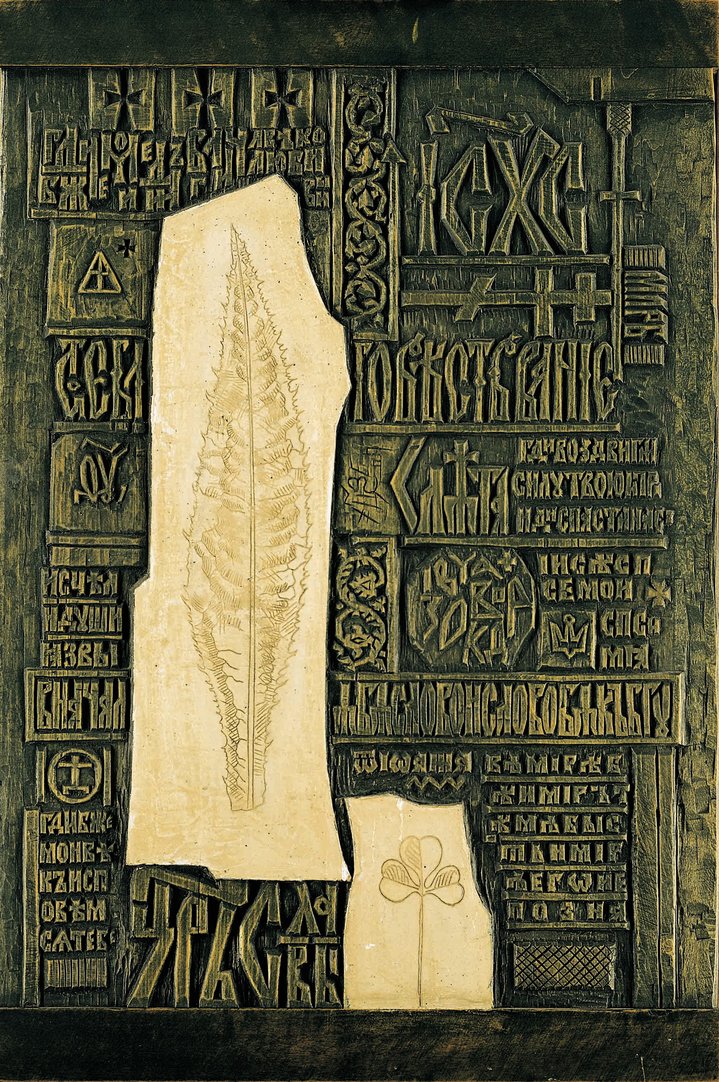

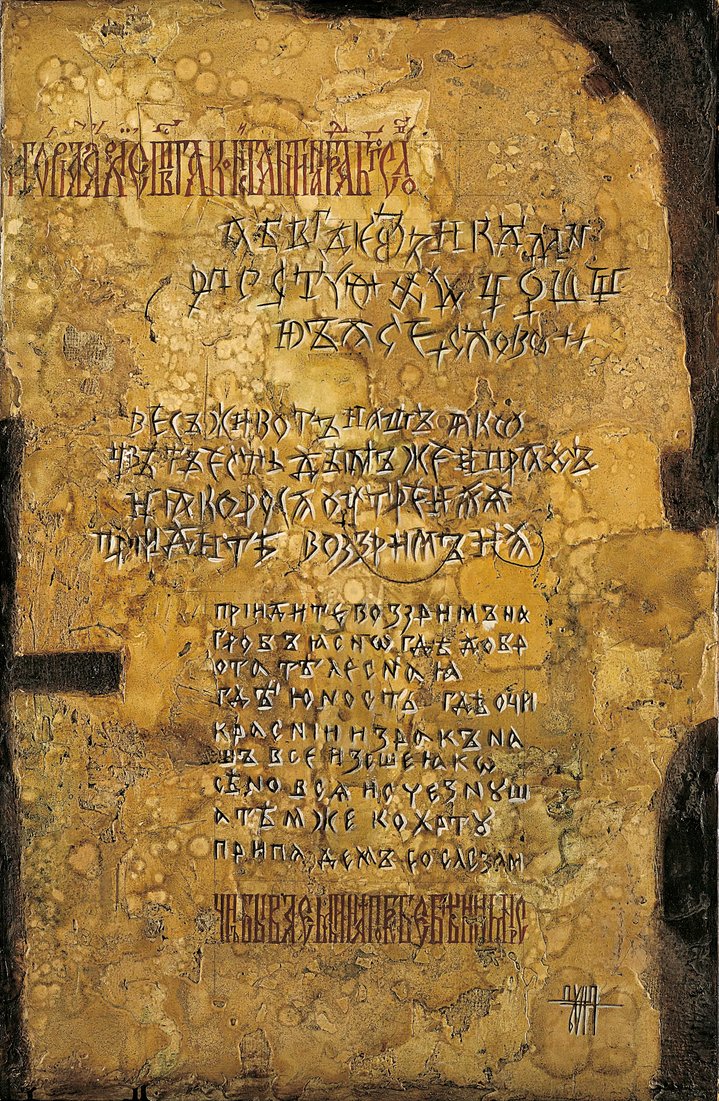

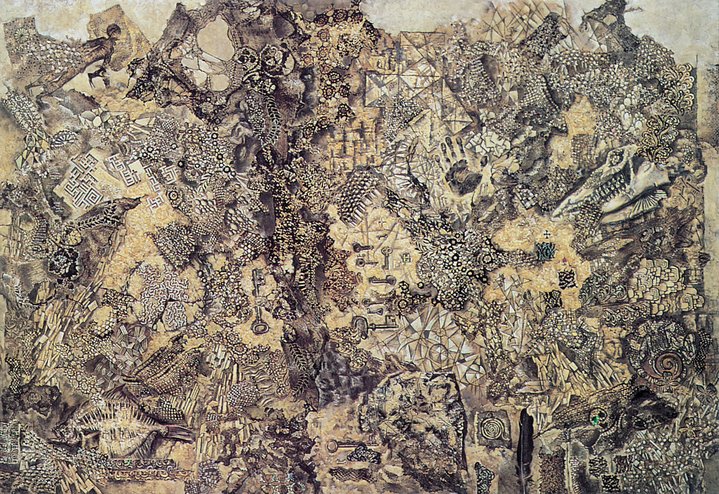

Dodge was not the only buyer of the art works Nina had brought to the United States on that trip. After the end of her exhibition, she also persuaded the New York Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) to buy several other works from her collection, including one by Dmitri Plavinsky (1937-2012).

Despite Nemukhin’s disparaging comments about Nina’s limited knowledge of art, he nevertheless held her in deep respect for the role she played in supporting underground artists and opening their eyes to the existence of another way of life beyond the limits of the Soviet empire.

According to Nemukhin, Nina herself once complained she could have followed in the footsteps of the great collector George Costakis (1913-1990) and might thus have bought famous names of the Russian Avant-Garde. “Why the hell did I instead get involved with your lot!” she groaned.

“Almost unlimited possibilities opened up for her,” Nemukhin admitted, saying she could indeed have chosen any one of the many options opened to her as a collector. Instead, she picked the least known group, the nonconformists. “Stevens chose us, deliberately and after a sober calculation. She demonstrated in every way that this choice was not easy for her, that she was tormented by a sense of dissatisfaction and doubts about the correctness of what she had done,” Nemukhin wrote. “As a novice collector, she had a number of important qualities: ambition, a strong character and perseverance, as well as a Russian origin… combined with the status of a ‘foreigner’, which strengthened all these qualities,” he added. Nemukhin’s conclusion was: “It seemed to me then that she was looking for a chance to express herself as a person, as something more than ‘the wife of a foreigner’. Collecting was a kind of drug for her, a way of overcoming the numbing boredom of everyday life... the most important thing is that she loved us, clearly empathised with our passions and seemed to see in the underground a special kind of embodiment of the ‘Russian idea’. Nina Stevens collected with the seriousness and tenacity of a man who has found the true meaning of life. Usually she cared little about commercial gain and never haggled... She was one of the first to pay real money (i.e. western currencies) for paintings. This seemed to us a true miracle.”

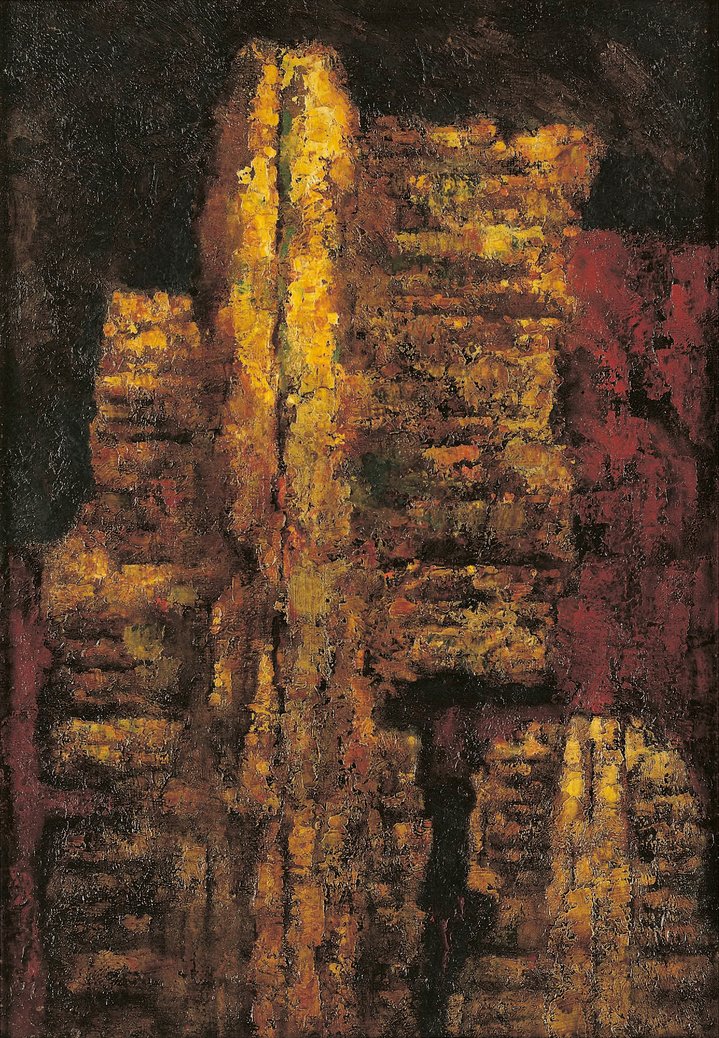

In addition to Plavinsky and Nemukhin, many other artists benefited from Nina’s patronage. Among her treasures were many canvases by the self-taught painter Vasily Sitnikov (1915-1987), as well as works by Oskar Rabin (1928-2018) and Anatoly Zverev (1931-1986). A friend of the family recounted how Nina’s grandson found a pile of sketches in a drawer and wanted to throw them in the rubbish bin, assuming they were drawings his grandfather had made as a child. It turned out that they were portraits by Zverev, a very prolific artist.

Nina also had a large number of paintings by Dmitri Krasnopevtsev (1925–1995), but they later mysteriously “disappeared”, according to one of her Russian acquaintances. A superb large canvas by the Georgian primitive genius Niko Pirosmani (1862-1918) had pride of place in Nina’s mansion, but the family eventually sold it at what was said to be one fifth of its real value.

Nemukhin mentioned rumours the KGB had ordered Nina to keep an eye on underground artists “to supervise us like troubled children”. Nemukhin didn’t comment on that rumour, but immediately after mentioning it he added he was “deeply convinced that independent artists owed a great deal to her, not only as an art collector and promoter in the dark 1960s, but also for letting them discover a delicious ‘American Paradise’, which made living in the Soviet one more bearable”.

Nina Stevens died in Moscow after a long illness in 2004. Her husband had preceded her in 1989. Her collection was sold by a grandson to unnamed Russian oligarchs. The mansion itself was later turned into the Embassy of Abkhazia, a Black Sea region that seceded from the Republic of Georgia. Russia is one of only five countries which recognise Abkhazia’s independence.