Will Fredo. You Don’t Live in the World. The World Lives in You, 2021. Performance. Courtesy of the artist. Photo Alexander Zhivotinsky, Geo.pro

The 6th Ural Industrial Biennale in Ekaterinburg (until December 5, 2021) has expanded its geography. A modest central zone is complemented by countless satellite sites.

The paraphrased quote from Ecclesiastes in the title of the Biennale - “A time to embrace and to refrain from embracing” - changed the meaning of the Biblical line to align more with the current epidemiological situation. We embrace, we shy away. And the word ‘we’ did not fall from the sky. The curators have used the first-ever dystopian novel, Yevgeny Zamyatin’s ‘We’, as the jumping off point for the main project, titled ‘Thinking Hands, Touching Each Other’. ‘We’, which inspired George Orwell, depicts a superstate - the One State - conquering the globe with absolute control over its citizens who are guaranteed “faultless happiness” and live under numbers instead of names. “The line of the One State - is a straight line. A great, divine, precise, wise, straight line - the wisest of lines...” was read in a German translation at the opening by Çağla Ilk, co-curator of the project with Misal Adnan Yildiz (also Turkish-born and co-director with her of the Staatliche Kunsthalle Baden-Baden) and Tel Aviv native Assaf Kimmel. And the project was opened by an evocative work on violence by Runo Lagomarsino (Sweden) - the letters WE nailed to a white wall. In the novel, disenfranchised citizens build the ‘Integral’, which will ensure Earth’s conquest of neighbouring planets. The exhibition, held again this year at the Ural Optical and Mechanical Plant (UOMZ), reflected a vision of futuristic technology in the tradition of science fiction writers of that era. The plant is part of the Shvabe holding of Rostec State Corporation (Russia’s main manufacturer of military equipment), partnering with the Biennale for the third time. Only this time, instead of the historic old assembly line that, in 2019, entered into dialogue with contemporary art as viewers wandered endlessly through its corridors, discovering more and more new works, art has taken over the modern assembly line, which looks more like an exhibition hall. Robots’ voices are heard from behind a partition assembling precision machinery. In front of it, in a marvellous space with views of local constructivism, are the exhibits, of which there are few.

The exhibition is human scale - easy to take in - but the big question is whether this scale corresponds to the status of an international biennale.

The exhibition extends from the nails on the wall to the barbed wire fencing of Turkish artist Hale Tenger’s project ‘We didn’t go outside; We were always on the outside / We didn’t go inside; We were always on the inside’. Devoted to the Kurdish question, this reflection on porous borders is a section of the exhibition space behind barbed wire with a guard booth. Tenger, who was “guarding” it, recalled being dragged to court after the last biennale in Istanbul and charged with insulting the national flag. But, there is a Turkish flag in the booth again. A few steps away, ‘It’s always light under the ground’ (2020), a photo project by Valentin Sidorenko (b. 1995), reproduces the archive of a mine in the Altai region, a reminder of the terrible working conditions of miners. An animated film by Nikita Seleznev (b. 1990), ‘Slowly Aging Children’ (2021), was inspired by the life of Leningrad toy designer and sculptor Lev Smorgon (b. 1929), who, thanks to toys, slipped through the fingers of censorship. International artists also dedicate their work to Soviet totalitarianism, which always seems timely. Sculptural portraits of Soviet leaders can be seen in a VR installation by German artist Clemens von Wedemeyer, who visited the studio of sculptor Zair Azgur (1908--1995) in Minsk, Belarus. When you enter the hall, do not step on the white canvas crocheted by Šejla Kamerić from Bosnia and Herzegovina, hearkening back to the war in Yugoslavia when all women could do is stay home and do women’s chores. And you have to endure the gaze of a grey-haired woman on a giant screen - a still from the film ‘Two Minutes to Midnight’ (2021) by Israeli artist Yael Bartana, about an imaginary female government (including Marina Abramović) that would surely be better at ruling the world than the men. Bartana is understandably among the stars of the show. So is Olga Chernysheva (b. 1962) whose project features a 2017 film she shot at the Chekhov Museum in Moscow. As is Marcel Duchamp Prize winner Clement Cogitore with his 2017 video ‘Les Indes Galantes’, made after his performance of the same name at the Opéra Bastille in Paris. In the opera-ballet, staged to the great music of Rameau, it’s impossible to take your eyes off of the hypnotic krump dancers on the stage.

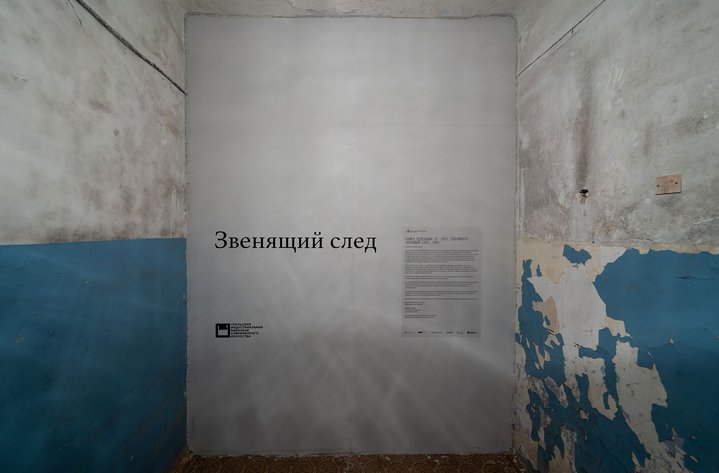

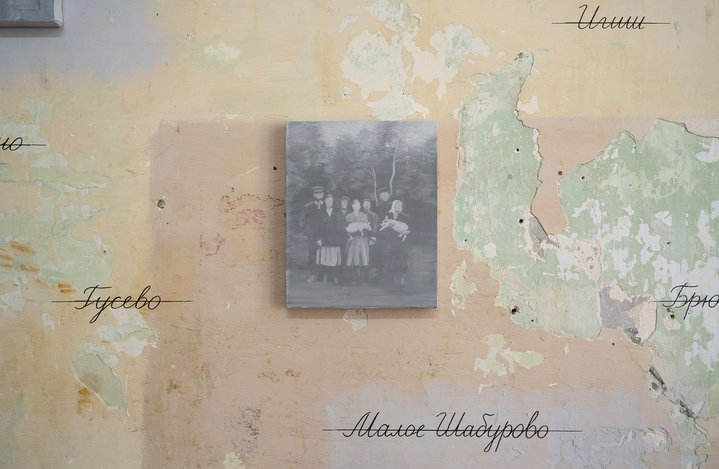

Almost all of the videos are shown at the former Salute Cinema, which let the Biennale in on the eve of its reconstruction, and the Metenkov House-Museum of Photography. Site-specific works have been introduced as interventions at the Main Post Office and the Museum of History and Archaeology of the Urals, but even these do not exhaust the list of the main project’s seven venues, among them the Ekaterinburg State Circus, which is hosting the performance art. The idea of making the Biennale smaller and more horizontal, expressed by its commissioner Alisa Prudnikova, is evidently a result of limited funds. This year the organizers had 100 million rubles, 20% more than during the previous Biennale, but the cost of everything has gone up significantly, plus the difficulties of travelling during the intermittent lockdowns - luckily, all three curators of the main project live in the same Berlin district of Neukölln and put it together remotely. Traditionally, there are few works by Russian artists - only 14 names in the main project (out of 52 artists and art groups from 23 countries). In 2019, by comparison, about a third of the 76 artists were from Russia. But the Ural Biennale always strives to bring foreign art to Russia rather than showcase its own. Local art could be seen in the special project ‘To Hug and To Cry’ at the Sinara Centre. This exhibition brought together artists whose applications were not selected for the main project and it turned out to be an excellent, witty show. The horizon of the Biennale also spread beyond the city’s borders to the neighbouring town of Nizhny Tagil with its three art residencies, to Kyshtym and to the neighbouring Chelyabinsk Region, where, in the settlement of Sokol, Pavel Otdelnov toiled at another art residence, dedicating the ‘Ringing Trace’ project - the highlight of the 6th Biennale - to the heroes and victims of the Soviet atomic project who worked there in secret Laboratory B.

6th Industrial Ural Biennale. A Time to Embrace and to Refrain from Embracing

October 2 – December 5, 2021