Moving on: the lost kinetic art of the USSR

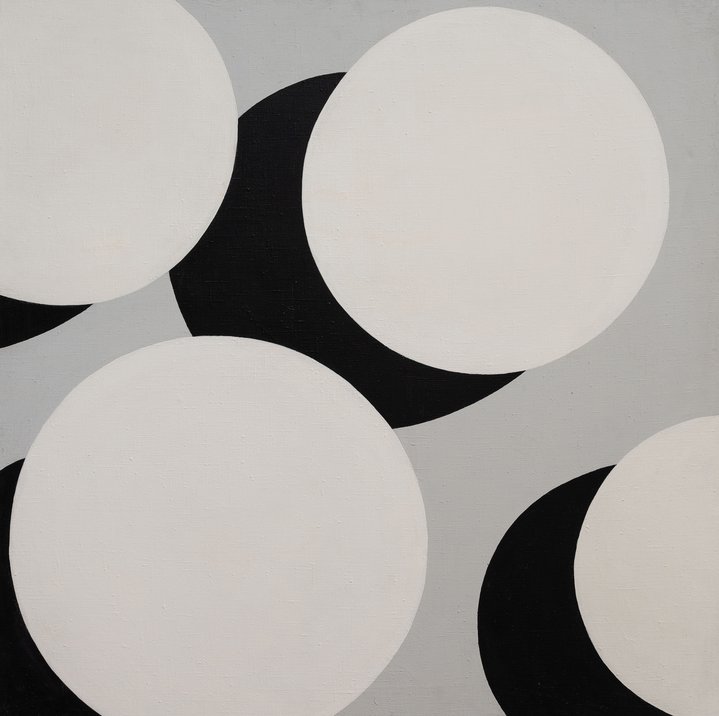

Francisco Infante-Arana Spirals, 1965. Tempera on paper, 104x52 cm

The art group ‘Dvizhenie’ (Movement) managed to bypass the stifling embrace of Soviet censorship and introduce kinetic art to a country where Socialist Realism was the only officially approved style. A newly opened exhibition at the State Tretyakov gallery highlights the group’s heritage, along with the works of its predecessors and successors.

In 1962, a group of Soviet art students gravitated towards each other through a common interest in metaphysics and rejecting the academic approach of art schools. What started as a circle of friends making modest experiments with abstract forms in the margins of their sketchbooks, eventually gained momentum and propelled that group to form a movement, called – guess what? – ‘Movement’, the meaning of the Russian word ‘Dvizhenie’. They devoted their common efforts to creating ambitious and far-reaching artistic experiments in kineticism, while the group itself moved and grew exponentially in a fusion of technology, society and the arts.

Yuri Gagarin, the first cosmonaut, had recently broken through the confines of the earth’s orbit and the then 19-year-old Francisco Infante (b. 1943), as he now recalls, felt suddenly compelled to record his ideas about the world’s infinity through art. He met the older, charismatic and savvy Lev Nussberg (b.1937), who was experimenting with symmetry and who eventually became the group’s self-proclaimed leader. They were soon joined by other children of what is known in Russia as the Thaw, introduced by the new Soviet leader Nikita Khruschev after the death of the ruthless dictator Joseph Stalin. It gave Soviet citizens a breath of fresh air. In the space age, technological progress became the ideology of the day.

By 1964, ‘Dvizhenie’ had become a self-proclaimed movement boldly stepping out with a breakthrough show called ‘Towards a Synthesis of the Arts’ staged in a Komsomol club, ‘Komsomol’ being a Communist youth organization in USSR. It used engineering and electronics to fuse media and various other genres in a multi-sensory approach to art. The exhibition’s design united both components and authors in creating a fusion between the collective and the individual, the object and its space, the viewer and the artwork. According to Nussberg, 16,000 people saw the show, an astounding figure for those times. “What we do is nominally called kinetic art, but the main thing for us is movement! We understand movement as change, relocation and interpenetration,” is how its manifesto was explained. “Movement itself is a form of expression!” is another way the group explained its goals in its 1966 manifesto.

Although that ‘Movement’ was labelled by some as Formalism, then a banned style in the Soviet Union, the artists were not seriously persecuted and their exhibitions actually turned into a launchpad. On the one hand, they gained respect and admission to underground artistic and intellectual circles. On the other, and much more surprisingly, they learnt how to penetrate official structures by presenting their projects as celebrations of scientific progress, demonstrations of the capabilities of collective labour or showing off the latest achievements in Soviet engineering and cybernetics.

The group consisted of some 30 participants, ranging from artists to scientists, engineers, musicians and dancers. They started securing prominent Soviet commissions, such as designing the public decorations for the celebration of the 50th anniversary of the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution in the centre of the city that was then called Leningrad.

“Just as ‘Dvizhenie’ walked the fine line between modernism and post-modernism, it also managed to exist on the boundary between officialdom and non-conformism,” the curator and art historian Kirill Svetlyakov noted. While censorship sometimes stepped in, by, for instance, cutting out the first act of a kinetic theatre performance or ordering a huge public installation of moving mechanical parts and changing lights created by Francisco Infante to be dismantled, such setbacks were far from crippling.

Misunderstandings often came as a blessing in disguise. Soviet officials and the public simply weren’t prepared to interpret Dvizhenie’s inventions as something belonging to the realm of art. That public therefore enthusiastically applauded the group’s stunning displays of light and metal as feats of contemporary engineering.

While slipping through the net of censorship and public scrutiny at home, the artists managed to export a different interpretation of their mission when abroad. They perceived themselves as the heirs of Russian Avant-Garde, as well as that of Suprematism and Constructivism.

Although Svetlyakov argues this connection shouldn’t be overrated, the younger generation of the ‘Movement’ was also connected to foreign kinetic and synthetic art in Western Europe and beyond. That propelled their ideas and dreams of a bright future thanks to a fusion of technological progress, art and society.

Was this the last Soviet Utopia? Perhaps. “If utopianism was a spent force by the mid-1970s, when, one might wonder, was the last time it was still an article of faith, particularly for East European artists, architects, filmmakers and writers who had once undertaken to provide images which might hasten its arrival?” That question was asked by David Crowley in his 2011 book ‘The Art of Cybernetic Communism’. The answer seems to be: “Dvizhenie”. Starting from 1976, however, the various group began to disintegrate. The movement had burnt bright, but it eventually fizzled out. Internal frictions over authorship and ownership became unavoidable. The members scattered in various directions. Nussberg ended up in the United States. Some, including Infante, continued to pursue either individual or new group projects. Others turned to design, engineering or even the priesthood.

Now practical hurdles make it hard to collate and exhibit any kind of encompassing history of the movement. Most of groups’ art works are lost and can only be shown as reconstructions.

The group’s legacy met a sorry fate. In contrast to its heyday, retrospectives or tributes have until recently been sparse. Attempts to revive kinetic art in Russia have been made through various shows in Vladivostok and St. Petersburg. ‘Future Lab: Kinetic Art in Russia’ exhibition staged in St.Petersburg’s Manege in February 2020, has recently been re-launched in an extended version now on display at Moscow’s Tretyakov Gallery.

However, how honest can these reconstructions be in contemporary museum settings? Many objects were tied inseparably to their original environments such as the Soviet Palaces of Culture and scientific institutes. “Kineticism is not just a new form of art … it is a new attitude to the World and to Humanity. There is no art outside man and no art without man. We are the pioneers,” is what Nussberg shouted in his manifesto, but will his voice be heard in a future where all visitors will have iPhones in their pockets? Svetlyakov asks whether a contemporary exhibition dedicated to that movement would be more honest and representative were it to consist of archival material, as well as unrealised projects, instead of trying to create a grandiose reconstruction.