Evgeniya Buravleva. Impressions of others, 2022. (Based on photo by Anton Pilipchuk). Oil on canvas. Courtesy of the artist

Closing time in Moscow’s museums

One-night shows in Moscow museums have become de rigueur in the Russian capital’s art scene. Exhibitions are shuttered not only after, but even before the opening night. A futurological show at the Museum of Moscow which – almost – opened on 5th of December is the latest in a phenomenon which seems to be on the rise.

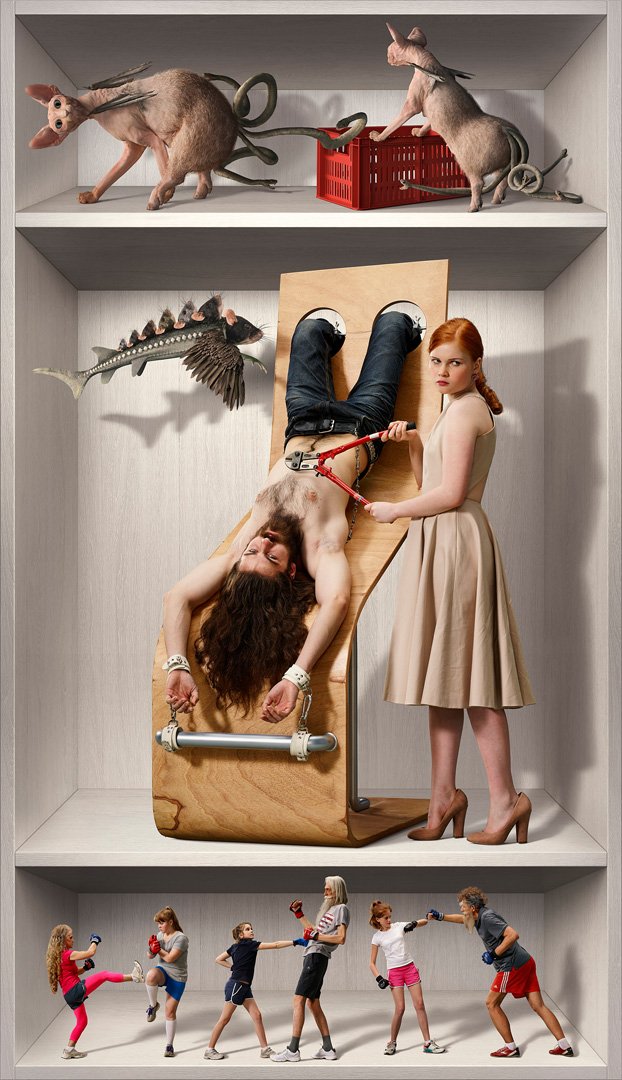

The exhibition ‘On chymeras and hybrids, cyborgs and people. A guide to inevitable future’ at the Museum of Moscow opened on the 5th of December. In partnership with the Triumph Gallery, it trailblazed hi-tech and new media art by both established and emerging Russian artists. Robotic installations and blinking screens were in cheerful abundance. Many local artists and art critics attended the opening reception. So far so good. Yet, those who were captivated by stories which appeared on social media about the show and ventured out into the harsh December frost to visit the following day met with closed doors. One such disappointed visitor was the artist Alexei Shulgin (b. 1963) who was told by the museum staff the exhibition was not open yet, and the installation was still in progress. A few days later, the museum’s press office told Russian Art Focus that ‘a decision about this exhibition has not yet been taken’. The exhibition was finally opened for the public five days after its official opening.

The Museum of Moscow is funded by the city government and so reports to its Department of Culture. As of Wednesday this week the day of writing this article, the exhibition’s doors remained firmly shut. One of its participants told Russian Art Focus that the Department of Culture had ‘banned half a dozen artists because they are on a stop list’. However, the artist added that ‘Everything will be in the catalogue, so when the abridged version of the exhibition opens, we’ll see immediately who was removed. Those people in the Department are stupid’. The Triumph gallery always publishes catalogues of the exhibitions it organizes in different venues, including state and city museums, at its own expense.

The existence of so-called ‘stop lists’ or blacklists was first made public by artist Pavel Otdelnov (b. 1980) who left Russia after 24th of February, and has since opened two exhibitions in the West that evoked a pessimistic view about contemporary Russian society. He shared in a recent post on social media that his works had been excluded from a museum exhibition on political grounds. ‘A few months ago, the staff of one museum in Russia wrote to me to say that they really wanted to exhibit my work in their exhibition. Not that I wanted to participate - not at all - but I wanted to support the staff, many of whom I know personally. They are still working and trying to do something under unbearable conditions. I know there are people with a conscience among them’, Otdelnov explained. ‘But today they wrote to me that the museum now employs some people who have ‘specially been trained’ to check every name. It transpired that the museum thought for a long time but decided in the end not to involve me because the risks were too high for them’. The existence of ‘specially trained people’ on the museum staff was also confirmed to Russian Art Focus by a museum employee who preferred to remain anonymous.

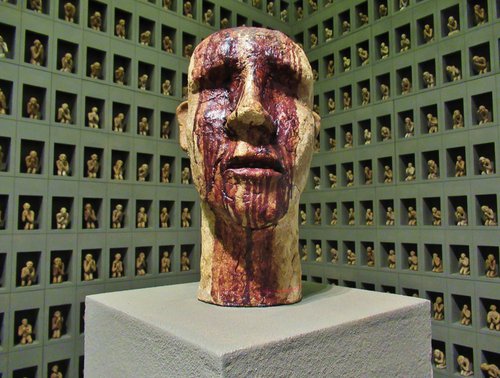

This is certainly not the first such incident in a major Moscow museum these days. In November, the Moscow Biennale was closed by the order of the Ministry of Culture on the eve of its official opening. It was due to take place at the State Tretyakov Gallery which has a national, ‘state museum’ status and reports directly to the Ministry of Culture, not to the Moscow government. The gallery’s official statement referenced the quality of exhibits not being on par with the level of a major state museum and their incompatibility with previously announced age restrictions (suitability for 6 years old and over) as the reason. Technical issues and a failure to install the show on time were also mentioned in internal correspondences between Biennale and the museum, published online by the Biennale’s director Yulia Muzykantskaya. The Biennale organizers also hinted that among the works on display which the Ministry found particularly alarming was a painting by Evgeniya Buravleva (b. 1980) dominated by yellow and blue, the colours of the Ukrainian flag. A video posted on the Biennale’s official social media account showed the artist herself explaining that the painting in question was nothing but a landscape, a realistic depiction of a field of crops under a blue sky.

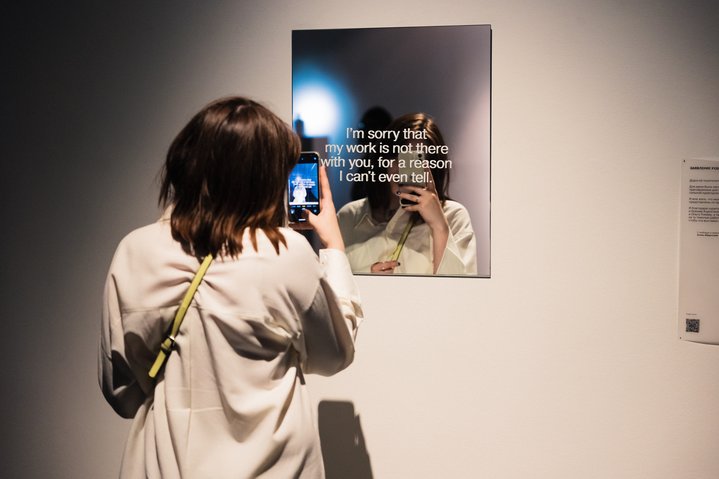

In July, the exhibition ‘Fragile Citizens’ at the Moscow Museum of Modern Art was also closed down on the evening after its opening. This show was curated by the students of a Master’s degree programme run jointly by the Higher School of Economics (one of Russia’s top state-run universities) and the Garage museum. Work on the show had begun two years earlier, yet in 2022 the context dramatically changed. Many young artists chose not to display their works, replacing them instead with notes such as, ‘The artist refused to take part in this show’ or ‘I am sorry that my works cannot be exhibited here for a reason that I cannot even mention’. This protest, though very low-key, was deemed unacceptable in a museum funded by the city. An official statement by the museum which was initially published on its website and subsequently removed, explained their decision: ‘This project had no political context and was privately funded. The students had been preparing the exhibition for two years, but in the process of forming the exhibition, the original concept was changed. As a result, the project introduced meanings and statements with political overtones, which MMOMA, as a state institution, does not consider acceptable to convey on its platform. Consequently, the organizers and participants jointly decided to end the project.’

In August, a show called ‘Signboard-Message’ which had been announced in public, was cancelled at the municipal ‘Na Kashirke’ exhibition space, part of the city-run network referred to by its acronym OVZ (United Exhibition Halls of Moscow). Its curator Kira Matissen, talking to a national Russian newspaper, said that a few art works had been removed by the administration of OVZ without any explanation. She managed to move the exhibition to an independent venue called the Zverevsky centre. Yet such private institutions have not been entirely immune to the plague of ‘one-night’ shows either. There, earlier this summer a group exhibition of artists calling for peace was also dismantled by its curators and participants overnight after the opening party. Information about it had leaked into ‘patriotic’ telegram channels. The police visited the centre the next day but all they found was an empty space with bare walls and Alexei Sosna, director of the Zverevsky centre was summoned to the Investigation Committee's office to explain.