The white stuff: snow in contemporary Russian art

Snow is more than merely a part of a winter landscape in contemporary Russian art. Very often it becomes a material, a symbol and a source of inspiration.

Grainy black and white video footage pans over a nondescript snow-covered rural landscape, the figure of a man, his back turned to the audience, dressed like an ordinary village drunk in a tattered coat, valenki felt boots and an ushanka (hat with ear flaps) bar one exception. He has two big white angel wings attached to his back. This “Snow Angel”, which gives the title of Leonid Tishkov’s (b. 1953) 1998 video work, clumsily shuffles through the snow, flaps his wings a little, jumps off a small hillock, conveying a sense of helplessness, cold and awkward loneliness, in all his movements. He eventually walks off into a field of snow that engulfs him, leaving the screen completely blank. This poetic and melancholy work, with a modest sense of self-irony, conveys so much of the Russian soul and the place snow occupies in it.

“Russia is associated with infinite white spaces, which are in a strange zone between the natural phenomenon and the metaphysical, contemplative white, in the zone of white contemplation,” art critic Boris Groys (b. 1947) once said in conversation with artist Ilya Kabakov (b. 1933): this exchange was recorded for posterity and later published as book, along with several other ones.

Snow is a blank canvas, and a blanket, a cover-up obscuring what ground lies beneath. Snow is a material for sculpture, from the earliest childhood. It is omnipresent and egalitarian. It is oppressive and ephemeral. It is cold and warm. Snow brings light at the darkest time of year. It is both very physical and metaphysical, optical and invisible.

A mandatory part of the winter landscape for many artists working with snow might not be so much a choice as an inevitability. In the late Soviet period, contemporary artists wanting to pursue such non-conformist genres as conceptual art, performance, installation or land art could not hope for any kind of acceptance from institutions, let alone popularity and media or public attention. On the contrary, they knew to avoid these at all costs, and heading to the countryside was one solution, far from the watchful eye of nosy strangers and potential eavesdroppers. There is no shortage of countryside in Russia, and its wide expanses have embraced generations of disenfranchised artists and poets, whereas social and political structures have let them down time after time. Suburban trains (“elektrichki”) offered a plentiful and cheap escape route. This was exactly the route taken by the burgeoning performance art group ‘Collective Actions’ with Andrei Monastyrski (b. 1949) at its helm. Modestly titled ‘Trips to the Countryside’, over a hundred such trips were undertaken over the course of decades, beginning in the mid-1970s. Carefully constructed actions or performances would be staged in empty fields and forests with only the members and friends of the group themselves for an audience. In wintertime (a lot of the time), their backdrop was a white blanket of snow and rows of frosty pine trees in place of museum settings and audiences, on the one hand pathetic and absurd, but certainly much more focused internalised and meditative to the point of a certain Soviet kind of zen.

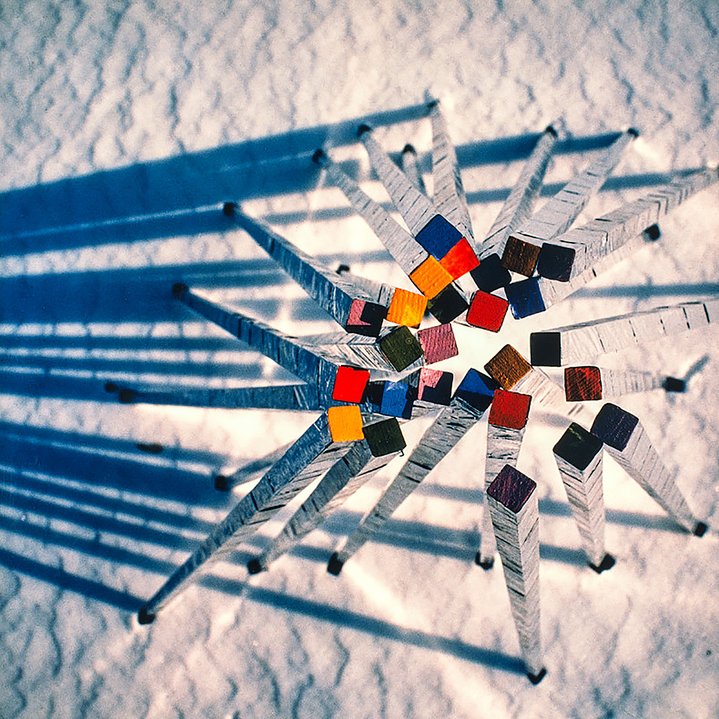

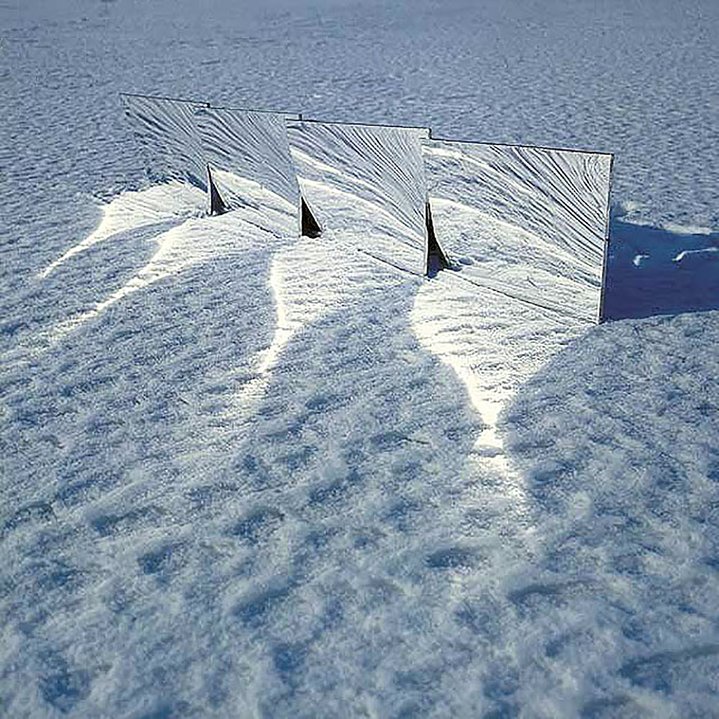

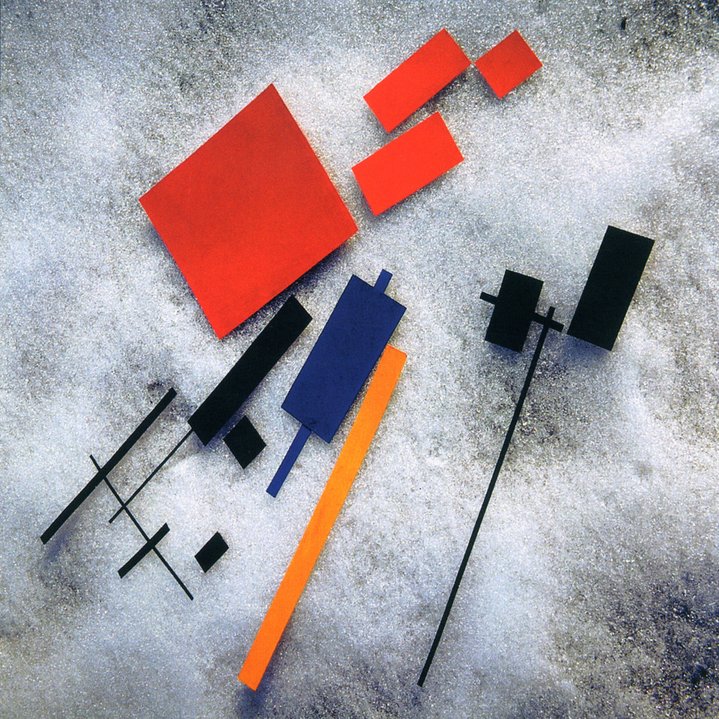

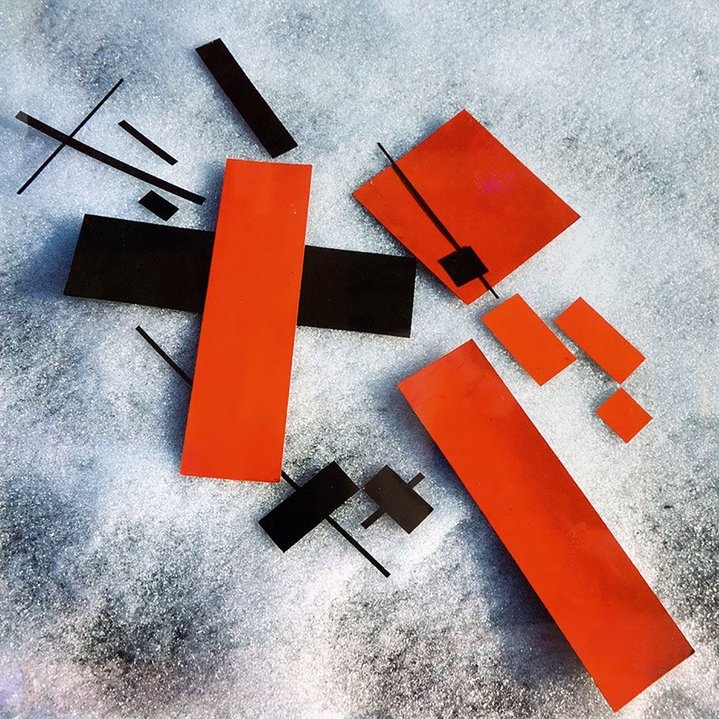

Francisco Infante (b. 1943), an experimenter in illusions and himself an op-artist of sorts, also escaped to the natural studio, but unlike the conceptual works of ‘Collective Actions’, his use of the environment is always optical, and thus, snow becomes a real rather than ideological blank canvas. Referencing the constructivist paintings of the first generation of Russian Avant-Garde artists, he recreated their suprematist compositions by arranging physical shapes on a bed of snow and photographing them. However, the snow is already melting, not pure white, just like the aged and crackled suprematist canvases, at closer inspection, which bear the signs of the material world.

Alexander Shishkin-Hokusai (b. 1969), a set designer originally, began creating contemporary artworks in the 2010s. Upon entering the art scene, he extended his real family name Shishkin, well known in the Russian theatre world, into a pseudonym which pays tribute to two widely popular artists, who incidentally also depicted snowy landscapes. However, he too found a welcome refuge in snowy forests: he initially placed large plywood cut-out figures of nude girls into the urban environment, but met with hostility and censorship. His method is simply to stick the figures into the snow, which can immediately create a theatre set, albeit without viewers, of whatever is desired.

Nikolai Polissky (b. 1957), was initially a landscape painter himself, until one day he realised that, boundless expanses of snow this is the main Russian material. He understood that he could become part of the landscape, work with it, change it, rather than just represent it with his paintbrush. Thus his land art career began in 2000 with ‘Snowmen’, an entire army of them descending along an empty field to the riverbank, conceived together with artist Konstantin Batynkov and built with the help of local villagers, whom he has been enlisting ever since for his monumental constructions, reviving and bringing fresh blood and talent to the village of Nikola-Lenivets, a beautiful but neglected corner of rural Russia that now hosts annual land art and experimental architecture festivals.

But when it comes to regional distinctions, foremost ownership of snow has to be handed to Siberian artists, for whom the element is a real trademark. Damir Muratov’s (b. 1967) project ‘United States of Siberia’, in the vein of Siberian Ironic Conceptualism, campaigns for Siberian independence with paintings and merchandise of proposed flags, crests and logos, as well as Siberia’s symbol, the snowflake. A younger Siberian, Natasha Yudina (b. 1982), posits her own eerie beauty as a self-styled gothic snow queen. She creates objects in which western cultural clichés and common objects are transformed to brave the Siberian climate and her ‘Venus de Milo’ is therefore covered in furs. Speaking to her audience in ethereal tones from the “snow mound”, she says in an interview on camera by Omsk curator Anastassia Kuklina: “It is very difficult to survive in Siberia: there are snowstorms, blizzards, bitter frost and a rogue bear roaming close by.” Her work perpetrates these myths. Like so many contemporary Russian artists who exploit popular clichés in their work, such as Communism, vodka, roaming bears, and snow. A double-entendre that allows them to satirize these stereotypes, but at the same time stick to a recognisable and exportable subject matter.