The secret castle

Tides are changing for the Vladivostok fortress, an enormous fortification on Russia’s Pacific coast which remains a mystery even to the locals but caught the attention of a Moscow photographer, Ivan Boiko. It is now being turned into a museum site

Photographer and exhibition curator, author of several landscape and environmental photography exhibition projects.

It is conventional to think of a fortification according to the affronts it has had to sustain. The thickness of its walls; the ingenuity of its placement in the landscape; its ability to deter foes and respond to changes in siege craft over time. Such are the terms that have been used to describe the fortifications of Vladivostok, a network of forts built mostly between 1889 and 1918, in the hills around Russia’s largest Pacific port. Although the fortress became an official heritage site in 1995, it long remained in various states of disrepair. The site received the attention of the federal government again, in December 2018. It has since become the country’s “easternmost federal museum,” providing an opportunity to narrate Russia’s military history in the region.

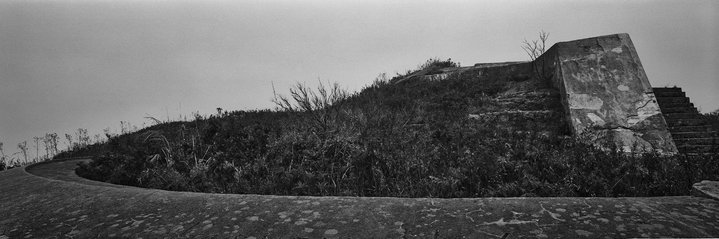

It was the fortification’s uniqueness in the history of Russian military architecture that also attracted the photographer Ivan Boiko to the site in 2010. But it was the the site’s life after active military use ended that he found most compelling. “The fortress ceased being a relevant functional object after World War II and started becoming a landscape, that is, an art object, all on its own,” he said. What struck Boiko, who has a deep interest in the relations between humans and the natural world, was the fortress’s simultaneous visibility and invisibility, both within the landscape and among the general public. “It’s an enormous site, but with the exception of a few specialists, almost no one knows anything about it. If you ask within the city where the fortifications are, most people will gesture towards the coast. But what’s interesting is that the city of Vladivostok is actually only a small element within the expanse of the fortifications.” Rather than ignore the paradox, Boiko explored it. His subsequent project, Fortress Vladivostok, combines his archival research and photographs of the site to bring us closer to a world that remains distant even to those who live within it.

Reflecting on his process of making the photographs, he spoke openly of how it inspired him personally: “This was the first time I saw the Pacific Ocean.” He also stressed the strange topographic mixture of open space and coastal hills, which decontextualize the concrete forms and make them difficult to read as fortifications. He visited the site twice, first with a medium-format camera in 2010, and again with a large-format field camera in 2012. The resulting black-and-white images convey the expanse of the coastline and the twisting, jumbled concrete forms within in.

Although Boiko’s photographs form a series, each image stands its ground as both a fragment and an image of the fortification’s own fragments, asking to be considered as such. Many artists in 19th century Europe and Russia used the romantic aesthetic of the fragment in their work as empire-funded archeological research and emergent nationalisms combined to produce strong preservation cultures. Boiko’s photographs are certainly less melodramatic than nineteenth-century depictions of decaying classical ruins, but they send a similar message. He hands us history that is already fragmented, catching us between the small available part and curiosity about the fortification’s previous condition — which may never have been whole to begin with.

That significant steps have been made to restore the fortifications came as good news to Boiko, in part because the initial form of his Fortress Vladivostok project included a petition to preserve the site. Yet, he spoke matter-of-factly about the ability of his photographs to inspire preservation. “I did not take them in order to ‘save’ anything.” Instead, he described his artistic ambitions as framing and altering the way viewers engage with the environment. “I believe that the general public does not know how to relate to historical objects. They approach something literally, in the best case here, as the site of war. It was my wish that they should engage with the site’s uncanny qualities as a landscape, to begin to perceive on a different level the context in which they live.”