The Quiet Radicalism of Vladimir Weisberg

Vladimir Weisberg. Masha Lebedinskaya, 1958. Oil on canvas. 88x64 cm. Inna Bazhenova’s collection

The most extensive retrospective of Russia’s metaphysical modernist is to be unveiled soon at the In Artibus Foundation, Moscow

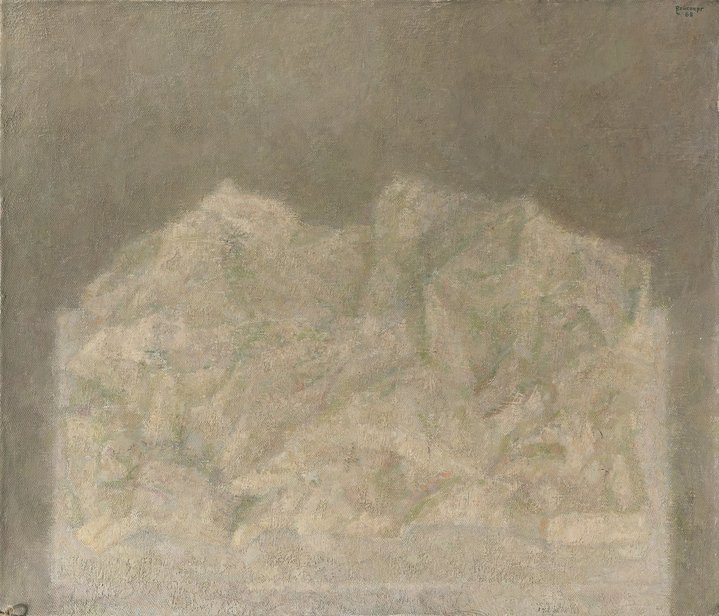

In 1915, Kazimir Malevich painted “Black Square,” a work which he thought marked the end of painting. Half a century later, Vladimir Weisberg attempted to find the beginning of it. The Russian-Jewish artist spent his forty-year career trying to find the fewest number of brush marks which could be made on a canvas before an image emerged, where nothingness became being. His “white on white” paintings were a response and a riposte to Malevich’s absolute blackness.

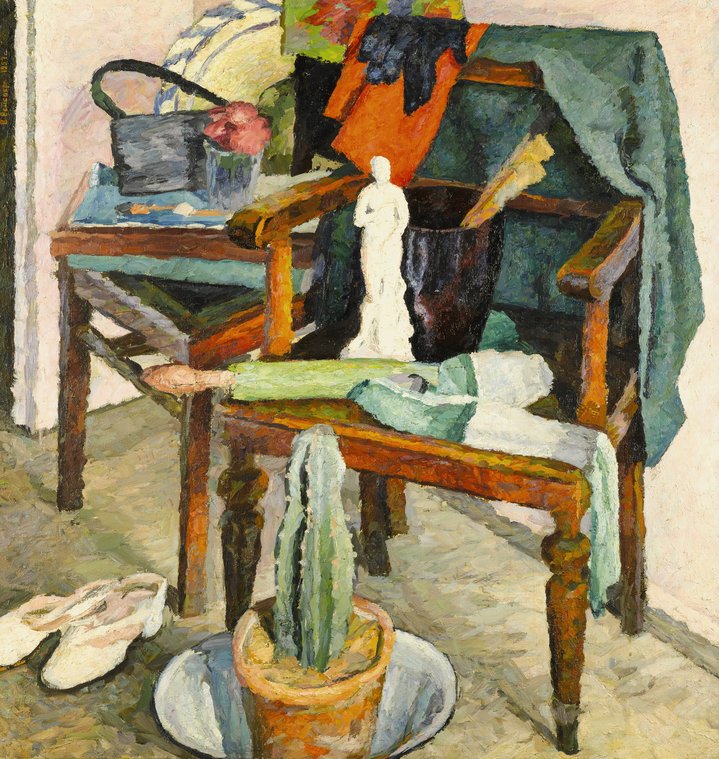

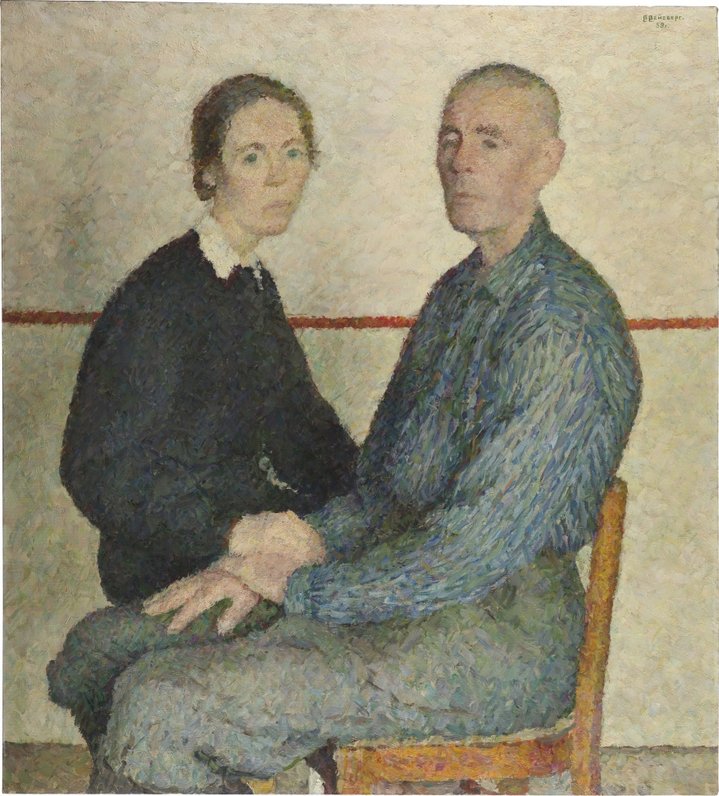

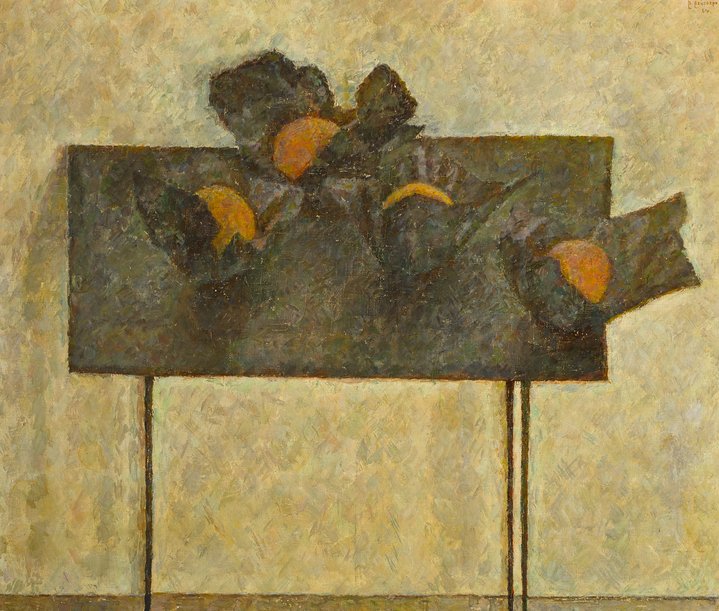

In fact, most of Weisberg’s works contain very little white. His still-lifes, portraits and nudes are awash with blues, greens, yellows, pinks and greys. But the colours are soft and muted, with minute differences in shade and hue, so that objects look as though they were being seen through a frosty window pane. “A work should become white, if all, and precisely all of its colours fall ‘into the groove’...when, all together, at the very end, they form a lasting counterpoint, a resolution, a harmonious agreement, in white.” For Weisberg, white was not so much a colour as a value, a truth.

Weisberg was born in 1924, just a few years after the Soviet Union was established, and died in 1985, a few years before it collapsed: he never knew a world without it. Yet he was far from being a Soviet Man. He was one of those rare Soviet auteurs, like Sofia Gubaidulina in music and Andrei Tarkovsky in film, who managed to completely eschew the pressures of political and creative conformism.

His colourful early portraits and later, nearly-monochrome still-lifes and nudes could hardly be further from the state-sanctioned style of Socialist Realism. Yet for the most part, the artist stayed on the right side of the authorities: in 1962 he was accused of formalism and pornography, but he avoided punishment and remained a member of the Artists’ Union of the USSR from 1961 until his death. During his lifetime, his works were regularly exhibited both in the USSR and abroad, from Israel to Germany and America.

Today, the largest private holding of Weisberg’s work is in the collection of Inna Bazhenova, and the largest public one in Moscow’s Pushkin Museum. This year, from February to July, they will join forces to stage the most extensive retrospective of his works to date, entitled “Nothing but Harmony.”

Weisberg wasn’t a member of “unofficial” or “non-conformist” artistic circles, either, nor was he engaged in conceptualist or “Sots Art” experiments led by other Moscow artists. His works are resolutely unconcerned with contemporary reality. Indeed, while he painted, he allegedly blocked out any sign of contemporary life, emptying his white-walled studio of all furniture except for an easel and covering the windows with thick curtains.

Rather than being labeled as an official or unofficial Soviet artist, Weisberg fits into the lineage of early twentieth-century European Modernism. His theoretical writings, such as his quasi-scientific 1962 essay “The Classification of the Main Types of Artistic Perception,” draw heavily on similar works by Kandinsky. Like him, Weisberg thought that painterly shapes and colours had a spiritual quality and that they could produce a certain existential harmony:

We see an object only through

The imperfectness of our vision.

With perfect vision we see

Harmony, rather than an object.

Weisberg practiced Cézanne’s injunction to “treat nature by means of the cylinder, the sphere, the cone.” His still lifes depict a flat surface with an assembly of three-dimensional geometric shapes. In this, he followed in the tradition of another obsessive painter of still-lifes, Italian artist Giorgio Morandi. For all three of these artists, separated as they were by time and place, still-lifes were not just about capturing the likeness of fruit and vases; it was a way of probing the very nature of things. Though modest in scale and subject, their works aspire to the metaphysical.

Weisberg’s nudes and portraits matched his still-lifes for tranquility. He demanded complete stillness and silence from his sitters. In the works, they emerge as ghostly and ethereal, like otherworldly beings. Weisberg also called his “white on white” works “invisible paintings” — seemingly a paradox or a joke, but in fact an invitation to the viewer to look closer and harder, both at art and at life.

Nothing but Harmony. Works of Vladimir Weisberg from the collections of State Pushkin Museum and Inna Bazhenova

Moscow, Russia

1 February – 28 July 2019