Stepping twice into the river

Re-staging an exhibition from the past in our contemporary context is a challenge only the bravest curators are willing to take on. In the run up to such a journey-in-time show at Moscow’s Museum of Russian Impressionism, aiming to transport us to New York in 1924, art critic and curator Andrey Shental reflects on the practice.

In the second half of the 20th century, the curated exhibition became a dominant cultural form. But only in the last couple of decades has it finally reached a truly mature state, with the emergence of a peculiar type or self-reflexive genre that is interchangeably called the “remembering”, “reconstruction” or “reenactment” exhibition. Early examples of this genre were already present in the 1990s, such as Stephanie Barron’s ‘Degenerate Art: The Fate of the Avant-Garde in Nazi Germany’ and ‘Exiles and Emigrés: The Flight of European Artists from Hitler’, but it was only in the 2010s and especially after Germano Celant’s resonant ‘When Attitudes Become Form’ (Bern 1969 / Venice 2013) that we witnessed a true reconstruction boom, as well as numerous critical publications on the phenomenon.

In her taxonomy of “remembering exhibitions”, Reesa Greenberg distinguishes between two major subcategories which she calls “replicas” and “riffs”. Replicas tend to re-assemble all the original contents of an earlier exhibition in the same arrangement as before. Riffs by means of pairing, multi-site exhibiting or mere reference create a more complex self-reflexive and performative statement, bringing to light contemporary connections. This taxonomy could easily be applied to the Russian context, although one must keep in mind the specificity of Russia’s past that was famously described by Margaret Thatcher as “unpredictable”. The rationale behind such projects, as Linda Boersma and Patrick Van Rossem observe, is to rewrite or reaffirm the existing canon. So in order to understand them, one needs to pay attention to the major historical periods or “points of bifurcation” in relation to which various reenact-ors — artists, curators, dealers, state and private institutions — politically and ideologically position and align themselves.

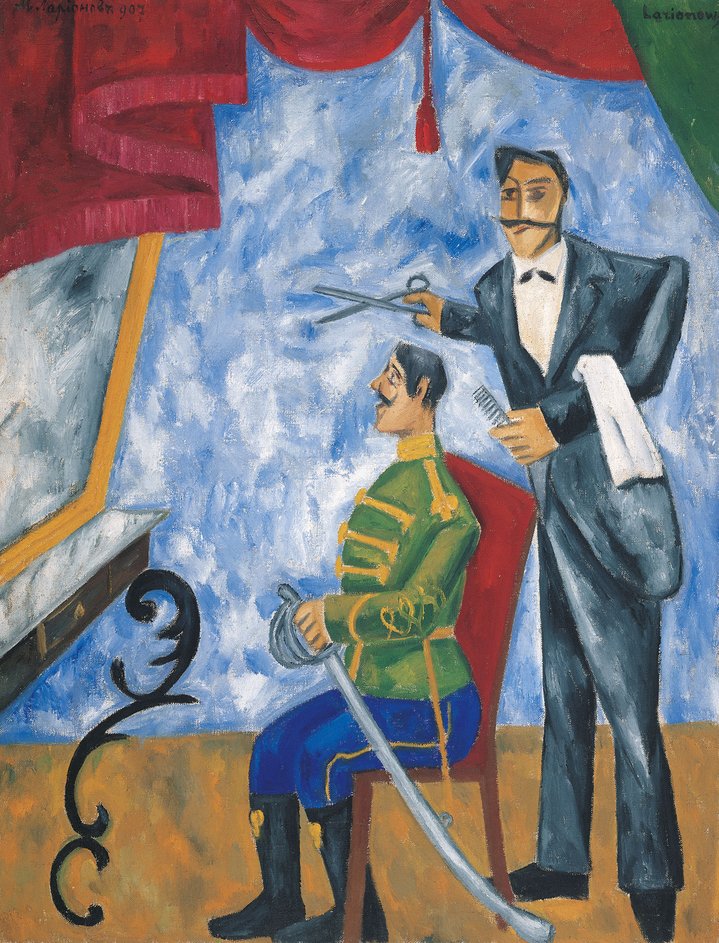

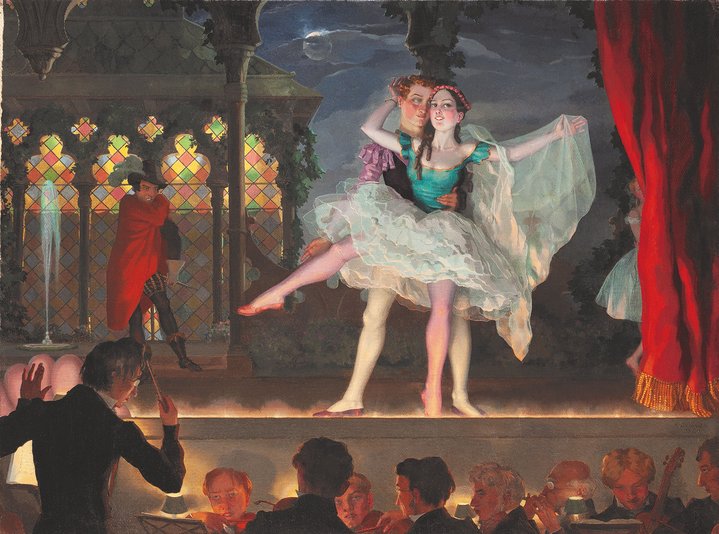

To my knowledge, the first example of a “remembering exhibition” in Russia was the reconstruction of the 1921 Second Spring Exhibition of OBMOKhU made by artist Vyacheslav Koleichuk (1941–2018) in 2006. This legendary exhibition survived only in two photos, but has been referenced in all key textbooks on the Russian avant-garde and is thought to have kicked off the emergent constructivism movement and prefigured many tendencies to come: from kinetics to minimalism. Thanks to meticulous work into even the original lighting, handling systems and plinths, these two basic archival images gained a kind of three-dimensionality, which was necessary for a full phenomenological understanding. However, the reconstruction does not convey one important aspect of the original. In the 1921 show, the objects were treated as profane things and visitors, so the legend goes, even hung their coats on them. Today, it is exhibited as a vitrine in the permanent collection of the State Tretyakov Gallery and visitors are not allowed to enter. The distance lends these objects with the false aura of authenticity that, according to Walter Benjamin’s famous statement, avant-garde art had tried to tackle. ‘Avant-garde. List No. 1. To the Centenary of the Museum of Pictorial Culture’ is a more recent example of a “replica” that celebrates another achievement of the early Soviet avant-garde. It reconstructs the final exhibition of the Museum of Pictorial Culture, the most radical and experimental art institution of that epoch. This artist-run museum, as if prefiguring the structuralist methodology of the 1960s, assembled artworks in an ahistorical and anonymous narrative of the evolution of pure form. Thanks to thorough research through archives, private collections and press, the team of curators managed to recreate six rooms of the last incarnation of the museum by bringing together artifacts from 23 museums. But this focus on provenance and loss that is epitomized even in the very title of the show ‘List No. 1’, indeed, contradicts the revolutionary intentions of the celebrated exposition that is to emancipate itself from the burden of traditional art and rewrite history from scratch. Another show that one could mention in this context is the upcoming research exhibition ‘Other Shores. Russian Art in New York. 1924’ that will bring 70 works to the Museum of Russian Impressionism in Moscow out of the 1,000 that were originally displayed at the Grand Central Palace in Manhattan (some of those which cannot be brought to Russia will be reprinted in the catalogue). This barely remembered commercial exhibition used the idea of “national school” as a strategy to integrate Russian art into the American art market. Curiously, besides religious art, artists associated with the Ballets Russes or emigre painters, it included those authors, who supported the Bolshevik regime, but with historic, retrospective, nostalgic or politically neutral works. Also, surprisingly for a viewer today, it did not bring representatives of the Soviet avant-garde or even abstraction, which was thriving at that time. Thus, today, it can be seen as an interesting case of commodification, before the socialist avant-garde became its most expensive desired commodity.

The historical avant-garde of the 1920s is largely perceived as a heroic period of radical aspirations and experimental audacity that was “caught on the run” or, sometimes, by more traditionally minded connoisseurs in nostalgic terms the “Russia we lost”. Typically, exhibitions remembering this period, thus, resort to the healing power of performative repetition in a form of positivist replica, where restoration or simple reassembling of the objects that were hidden or destroyed seem to be a mode of compensation for this collective trauma. But, the very reconstruction of an avant-garde exhibition seems to be a contradiction in terms, since it intended to overcome tradition, negate authenticity and focus on processes instead of individual objects. Contrary to the intentions of their authors, the Second Spring Exhibition of OBMOKhU and ‘List No. 1’ do not repair injustices of history, but fetishize those artworks for the sake of their museification. The former’s commissioning the reconstruction of a well-established artist, or latter’s foregrounding the institutional inheritance of the collection impose continuity of tradition, instead of revolutionary rupture. In this context, celebrating arts patronage, ‘Other Shores’ seems to be a more coherent reenacting endeavour, since it does not flirt with the avant-garde, but openly embraces traditional easel painting, drawing and sculpture. Symptomatically, the last room of ‘List No. 1’ presented huge reproductions of the Complex Marxist Exposition that took place at the Tretyakov Gallery in 1931, where these works were exhibited as bourgeois and decadent. This exhibition, which presented the works for the last time before they went into storerooms for decades, in fact functioned as a tragic post-scriptum to the history of early curatorship. But the same Complex Marxist Exposition and its author Aleksei Fedorov-Davydov were central figures for another remembering Moscow Diaries (Moscow Museum of Modern Art, 2017), exhibition a collaboration between two institutions: the anonymous Museum of Modern Art and Centre for Experimental Museology.

Compared to the two exhibitions above, it should be categorized not as a “replica”, but as a “riff”, since it used elements of reconstructions as a commentary in a more complex meta-statement on the way history is written. Namely, it presented two historical reenactments assembled not of originals, but of deliberately cheap copies. The first was Cubism and Abstract Art, originally organized by Alfred Barr at New York’s MoMA in 1936, the second was that of Fedorov-Davydov’s experiment. Presented close to each other, they clashed two antithetical paradigms: a linear (bourgeois) history of art (more akin to the Museum of Pictorial Culture) and a (marxist) dialectical model, attributing artworks to certain classes and historical periods. As for the 1930s, the majority of Western, as well as post-Soviet art critics, historians and curators perceive it as rappel a l’ordre, a negative and anti-modernist period of neo-conservative revanche. However, some of them tried to see it from a more affirmative or at least complex angle. Most famously, Boris Groys understood the Stalinist gesamtkunstwerk as a logical and immanent continuation of the historical avant-garde’s impulse to merge life and art. This provocative point of view could be more resonant with a younger generation of researchers (particularly, the ones associated with Experimental Museology), artists (as in ‘Closed Fish Exhibition. Reconstruction’ that I will touch upon later) or even young privately-funded institutions, such as the ‘V-A-C Foundation’ who sponsored that project. So, the Tretyakov Gallery presented Complex Marxist Exposition with a self-accusatory tone (similarly to Barron’s Degenerate Art), whereas Moscow Diaries took it apologetically as a first curatorial project avant la lettre, positioning it within a much wider context of competition between Soviet and American aesthetic paradigms. One could say that in this quest for one’s own place in the dominant art historical canon, the restaging of the 1930s could be a way to assume a meta-position, not within art history but somehow above it.

One of the most ambitious initiatives to commemorate art of the past was commercial gallerist Elena Selina’s two-partite project Reconstructions (Ekaterina Cultural Foundation, 2013 and 2014). Chronologically split in two halves of the decade, it presented the major Moscow private gallery shows of the 1990s. Besides the actual exposition, the project was followed by the publication of two voluminous catalogues with exhaustive information on this epoque, made in collaboration with Garage museum. What is significant about it, is the adherence to a historical objectivity that goes hand in hand with the complete frivolousness of its presentation. What used to be singular entities scattered across numerous locations and stretched across five years, were all accumulated in one space and experienced by the viewer simultaneously as if it were a group show. In other words, this “riff ” did not pretend to be a factitious copy, but was structured dynamically as in actual human memory.

The most recent example of a “riff ” show is the Closed Fish Exhibition. Reconstruction made by Baza art school tutors and students at Moscow’s Voznesensky Centre (2020–2021). This project was a tribute to another chapter of Russian art history, namely the works of Elena Elagina (b. 1949) and Igor Makarevich (b. 1943), representatives of the middle generation of Moscow conceptualism. In 1990 they made a project called Closed Fish Exhibition that, in turn, referred to the eponymous exhibition of realist drawings that took place in 1935 in Astrakhan. The new edition included one actual drawing from the 1935 show, reproductions of Elagina & Makarevich pieces of 1990, homages to them made by different students as well as curator Yan Ginzburg’s own works that looked quite similar to Moscow conceptualist assemblages. While for Elagina & Makarevich reconstruction was a pure “blind” linguistic game based on the titles from the nomenclature of works, for the younger generation of artists, the material reality played a crucial role. They not only found certain original works from the 1930s show, but also made research about the current state of industry of Astrakhan. Nevertheless, seen all together, it clashed temporalities, decades and styles, as if stating that any historical reconstruction is ahistorical and unreconstructable.

Being so recent to us, the first post-soviet decade does not allow its reenactors to pretend to be authentic and historically accurate, leading them to more rhizomatic and speculative structures. This decade was characterized by critic Gleb Napreenko in psychoanalytic terms as a “primal scene ” of the current regime and “institutional and symbolic vacuum” by curator Viktor Miziano. That is why it attracts various actors of the art field to fill it with mythmaking and a kind of “dreamwork ”, where one stages oneself within this shaky canon. For gallerists, it was important to push aside the public sphere, that was the privileged site of Moscow actionism, and move the private market to the centre stage (Reconstructions). Similarly to the Museum of Russian Impressionism that supported Other Shores to restore the ruptured history of patronage of modernism, the privately funded Garage Museum worked on the publication of the Reconstructions catalogue to reaffirm its monopoly on the history of Russian contemporary art. Simultaneously, for practicing artists and curators such homages to the transient figures between conceptualism and contemporary art is a tactic of narcissistic self-historization and self-aggrandizement (Closed Fish Exhibition. Reconstruction). The concatenation of historical references is the win-win solution to get into historicizing exhibitions and historicizing texts like this.

Other Shores. Russian Art in New York. 1924

Museum of Russian Impressionism

Moscow, Russia

September 16 – November 16, 2021