Crossing the sea of discord

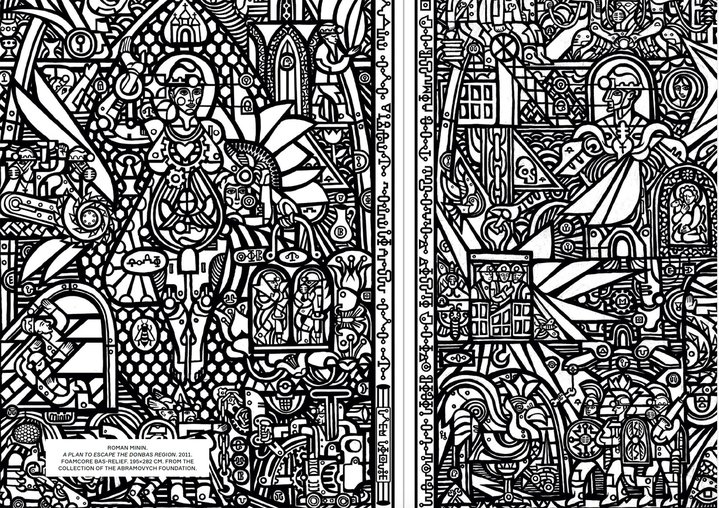

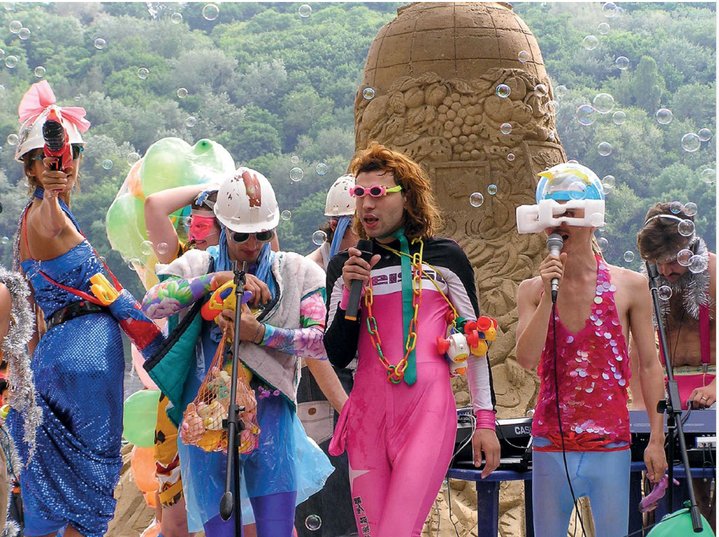

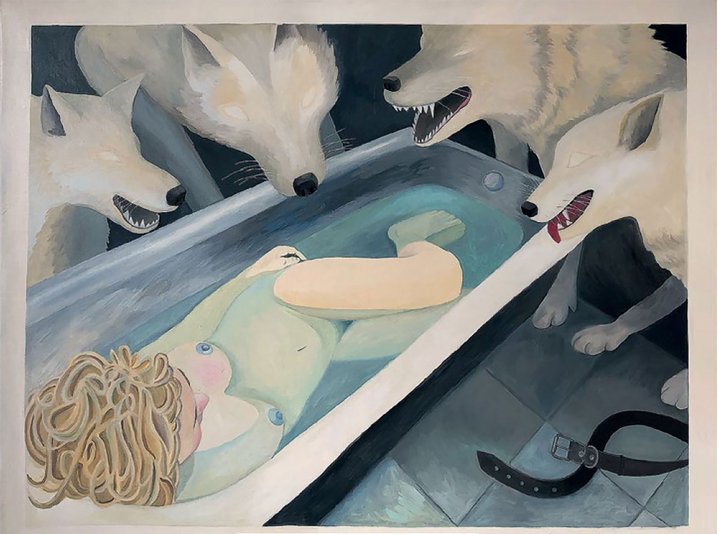

‘Permanent Revolution’, a history of Ukrainian art written by art historian and curator Alisa Lozhkina was recently published in English: a dazzling mosaic of numerous art groups and movements in the dark background of this nation’s turbulent history.

This magnum opus by Ukrainian art historian, curator and frequent contributor to Russian Art Focus, Alisa Lozhkina, impresses by its mere scale, even before you open it. Although, the author claims her publication “does not pretend, under any circumstances, to try and cover all the figures and events in Ukrainian art”, its encyclopaedic ambitions are too big to hide. This 544-page behemoth of a book covers 140 years of the nation’s art, from the late 19th century to the late 2010s. First published in Ukrainian and French, it was recently translated into English by the Art Huss Publishing House. The author, who is currently based in California, tirelessly educates Western readers on local contexts. The political and historical background to the art scene is described in such minute detail that the book could double as a history textbook. It is further enlivened with snippets of daily trivia, for example, we are told how, in the 1990s, artists did not trust curators because the word “curator” was the official title given to KGB officers who were surveilling bohemian outsiders.

Yet, Lozhkina’s writing somehow manages to remain exhaustive, without becoming boring. She’s an excellent storyteller, who never fails to make one feel that truth is stranger than fiction. Her unhurried art historical narrative is peppered with amusing observations, such as: “Alcohol was the drug of choice in bohemian Lviv, but in Yahoda’s case it was more than just a hobby.” Lozhkina parades before the reader’s eye an almost Dickensian procession of eccentric and tragic characters. Such as the painter, performance artist and street philosopher Fedir Tetianych (1942–2007), who “once arrived at an official session of the Union of Artists dressed as an alien”. Or Bruno Schultz (1892–1942), an artist who was arrested by the Soviet authorities “for using yellow and blue in his painting, the colours of the Ukrainian National Republic’s flag” and survived only to be shot a few months later during a Jewish pogrom, instigated by the Nazis. Or Mykola Hlushchenko (1901–1977), a painter and a spy, who, as rumour has it, was personally acquainted with Hitler and even gave him painting lessons. “In 1940, while preparing an exhibition of Soviet folk art in Berlin, Agent Yarema (the artist’s secret service alias) found out that Fascist Germany was preparing to attack the USSR. Hlushchenko’s report arrived on Molotov’s and Stalin’s desks, but they ignored it,” the author adds matter-of-factly. In the next chapter, an astounded reader learns how “cement trucks poured more than 300 loads of concrete over the almost finished relief” called the ‘Wall of Memory’, in an incredibly brutal instance of Soviet censorship. “To this day, the concrete-covered ‘Wall of Memory’ still stands next to the Kyiv crematorium,” Lozhkina concludes with eerie calmness.

The author stresses that her book is written “from a subjective standpoint”. And, indeed, this subjectivity shows. In a passage dedicated to Viktor Pinchuk, an oligarch who had once toyed with an idea of founding a museum of Ukrainian contemporary art, but then shifted his focus to international blue-chip artists, she observes in a tone of caustic reproach that “for a tenth of the price of one of Damien Hirst’s artworks, a favourite of Pinchuk’s collection, it would have been possible to create a quality museum of the latest Ukrainian art”. The author’s disappointment is almost palpable.

Names in the book are spelled according to the rules used for transliteration of Ukrainian names, which might be puzzling for the reader more used to Russian-style spelling. It takes a moment to realise that Oleksandra Ekster (1882--1949) and one of the so-called “Amazons of the Russian Avant-Garde” Alexandra Exter are the same person. Yet, the author’s patriotic efforts stretch far beyond spelling. One of the tragic paradoxes of the Ukraine’s history is that it became an independent state only in 1991. During the period of the Soviet empire, the art scenes in the Ukraine and Russia were closely intertwined, especially in Kyiv and Kharkov, with their huge Russian-speaking populations. Many artists moved to Moscow, capital of the USSR, for better education and career opportunities, as well as various personal reasons. “...this or that artist moved to Moscow” reverberates throughout the pages as a sort of refrain. Yet, Lozhkina finds place for all of them in Ukrainian art history. In certain moments, such as when, while writing about Kharkov, she mentions the poet and writer Eduard Limonov (1943--2020), who was born in Dzerzhinsk in Central Russia, wrote in Russian, moved from Kharkov to Moscow at the age of 24 and spent most of his life in Russia and America, one can’t help but wonder if the author’s patriotism is a stretch too far.

The constant references and comparisons with Russia may seem almost obsessive to a Western reader who is not very familiar with the interdependent relationship between the two countries. Lozkhkina quotes Russian art critics Ekaterina Degot and Viktor Miziano extensively and uses phrases, such as “The Kyiv squats differed from those in Moscow in that they were less focused on the external observer” can be found in every chapter. The author never misses a chance to highlight Ukraine’s superiority: “In the summer of 1967, long before Moscow’s Bulldozer Exhibition of 1974, the duo Sychyik+Khrushchik, made up of artists Stanislav Sychov (1937--2003) and Valentyn Khrushch (1943--2005), arranged the first non-conformist ‘fence exhibition’.” Yet, these personal biases and passions reflected on the pages of this book may be, to steal Lozhkina’s own words - used albeit on a different occasion - “its weaknesses, and at the same time, its strengths”. One can feel the blazing enthusiasm and high hopes of the author, as she walks across the riotous Maidan, when stumbling upon phrases such as: “The protest city behind the barricades became an all-encompassing art installation.” In the end of the day, wars may break out, state borders shake and empires fall, yet the love for one’s country and its art is something that remains. Probably, this book will remain, too.

Alisa Lozhkina. Permanent Revolution: Art in Ukraine. 20th to the early 21st Century

The PDF of the book can be downloaded free of charge from the website of the ArtHuss Publishing house.