Agitfarfor: the people's porcelain

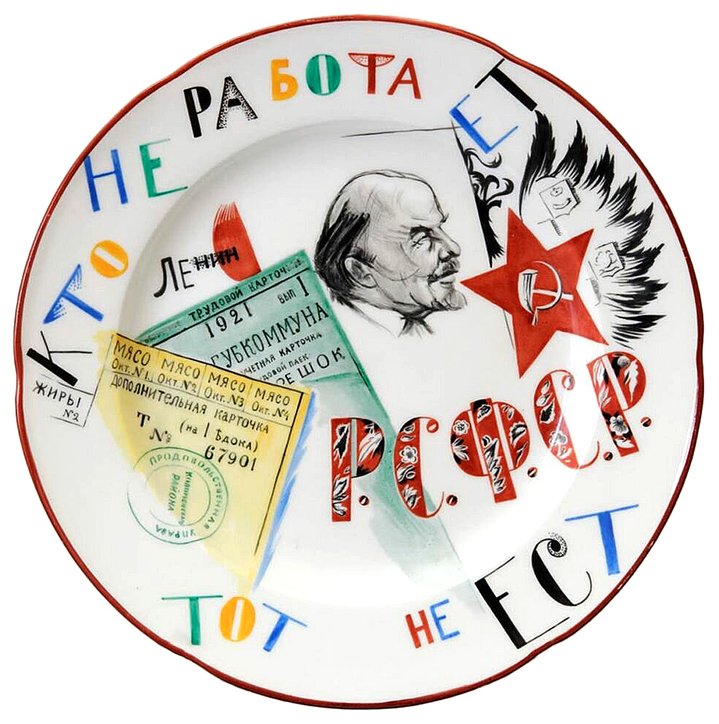

Veniamin Belkin. Dish “Blessed is the labour of free”. Porcelain. Sergey Chekhonin. Dish “RSFSR”, 1922. Porcelain. State Porcelain Factory

How the propaganda porcelain industry conceived by the Bolsheviks turned into an art product coveted by wealthy Western collectors.

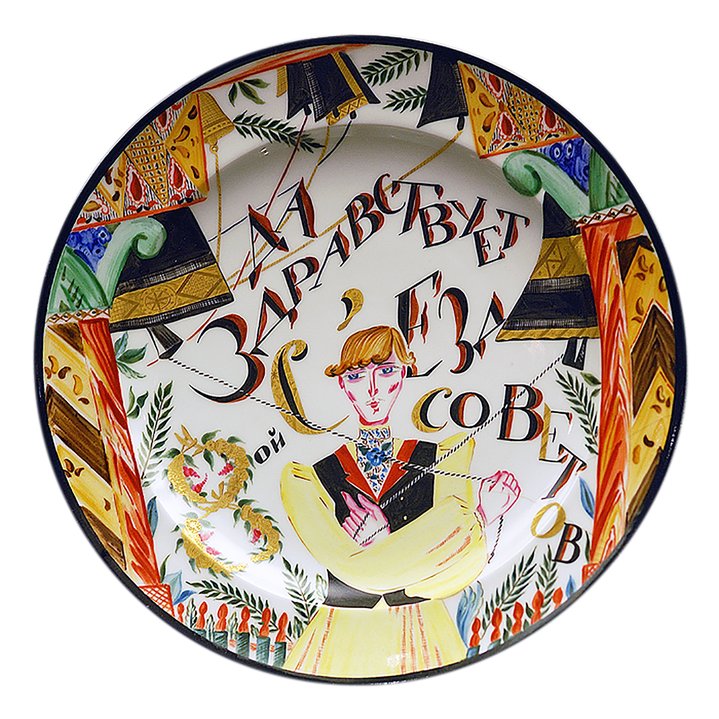

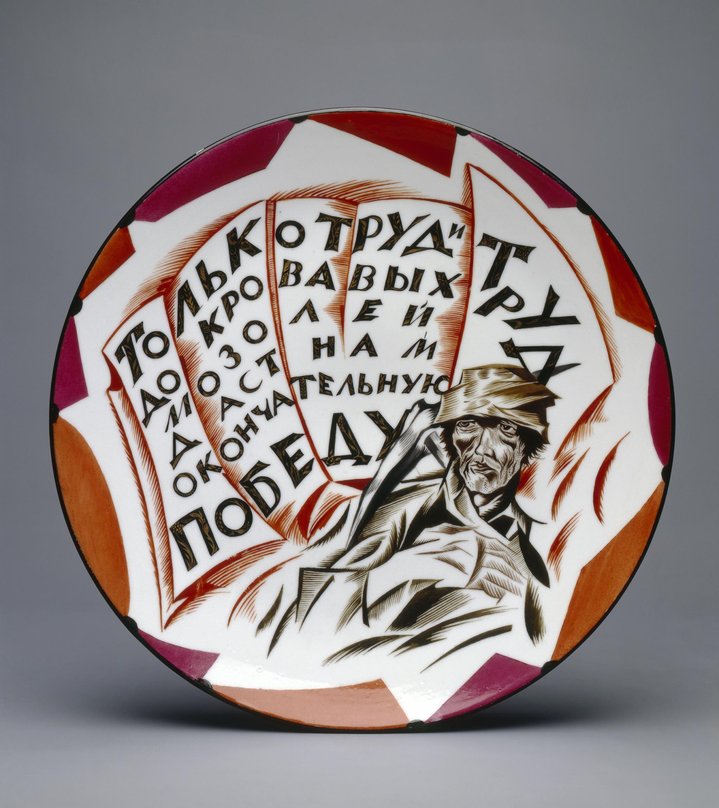

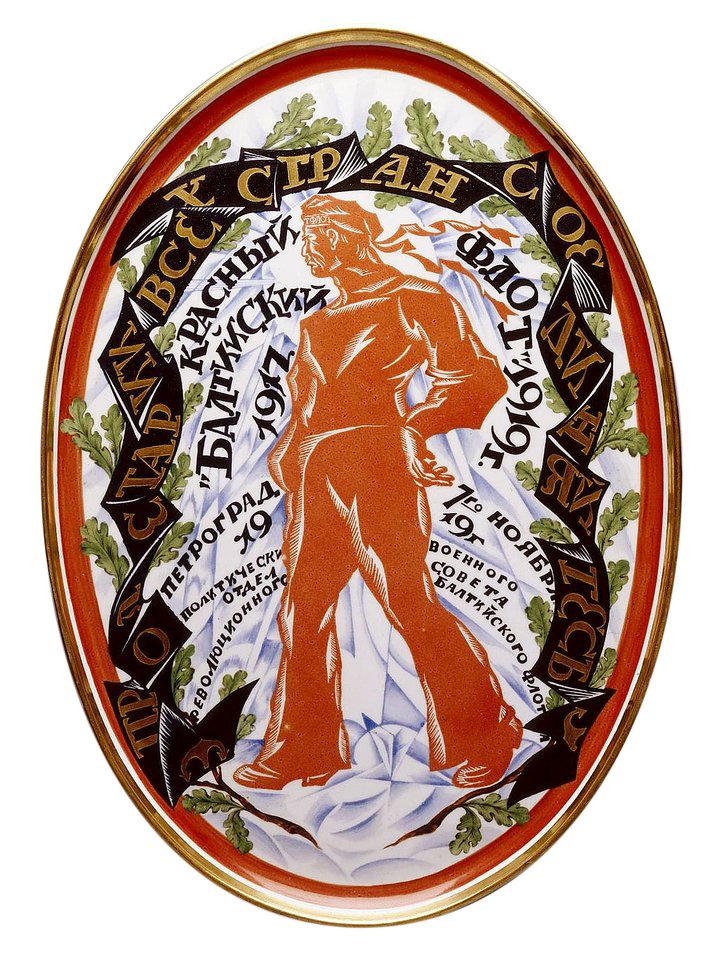

Agitfarfor, or propaganda porcelain, is a comparatively narrow yet compelling Soviet cultural relic, created by a concurrence of factors: ideology, manufacture, bravado and sheer artistic talent. The resulting objects are unmistakable, crisp porcelain dinner plates and platters emblazoned with red banners bearing revolutionary slogans, hammers and sickles, intertwined with foliage and gilding from a decorative past, teapots and cups in constructivist angular shapes and previously coy mantelpiece figurines now depicting heroes of the revolution. They are the highly colourful symbols of a long-forgotten politicised era whose appeal stretches far beyond the realm of the usual connoisseurs.

Porcelain, the “White Gold” invented in ancient China, had mystified Europeans for centuries since making its way into royal households through the Silk Road. Its recipe remained a coveted secret. It was in 18th century Germany that its code was broken, an achievement which set off a frenzied race by scientists, technicians and entrepreneurs to commercialise this philosopher's stone. Russia caught up in 1744, when the Imperial Porcelain Factory was founded in St. Petersburg by Empress Elizabeth. The brain behind this innovation was an ingenious young scientist named Dmitry Vinogradov, who managed to come up with the necessary formula. Unlike his lauded European counterparts, this Russian inventor was not rewarded in his homeland. Maltreated and suffering from alcoholism, he died aged only 38. Very little is known about the man single-handedly responsible for initiating one of Russia's proudest trademarks.

To coincide with the factory’s 275th anniversary, the State Hermitage Museum has mounted a retrospective, recalling that institution’s history from its inception to the present day. It will be on show until 5 April, 2020.

The factory worked exclusively to supply the Tsar’s family, making elaborate dinner services. After the 1917 revolution, the Bolsheviks seized the factory, changing its name and its target audience. The young state had an insatiable thirst for propaganda and was determined to disseminate it on any surface that could bear it. The large stock of yet unpainted whiteware provided a perfect canvas. Plates could carry political messages as well as food. Thus, the porcelain destined for royal receptions was intercepted by the revolutionaries and converted into ideological plates to inform proletarian minds, eyes and stomachs. These conversions are easily identified, as the front of the plates depicts workers and party leaders, whereas the reverse sides bear a Tsarist imprint stamped before the Revolution.

The factory was placed under the control of Anatoly Lunacharsky (1875–1933), the Kommissar in charge of the Ministry of the Enlightenment, responsible for many early Soviet cultural experiments and innovations after the revolution. It was renamed the Lomonosov Porcelain Factory in 1925. As a new era began, hosts of artists came to create “agitfarfor” (a portmanteau term for propaganda porcelain), which flourished in the ensuing decade. Work at the factory provided a means of survival during some of the toughest and hungriest years in Soviet history. The factory thus became a shelter for artists from all walks of life.

The roll-call of talents who worked there includes Kazimir Malevich (1879–1935), Suprematists Ilya Chashnik (1902-1929), Nikolai Suetin (1897–1954), sculptor Natalya Danko (1892–1942), eclectic primitivist Alexandra Shekatikhina-Pototskaya (1892–1967), decorative artist Rudolf Vilde (1868–1938) as well as Mikhail Adamovich (1884–1947), Trifon Podryabinnikov (1887–1974), Maria Lebedeva (1895-1942), Aleksei Vorobyevsky (1906–1992) and Zinaida Kobyletskaya (1881–1957). Of course, this wasn't Russia's only ceramics factory, many others caught up with producing ideologically themed dinnerware after their nationalisation. In fact, propaganda of sorts on porcelain existed before the revolution, too, with several commissions celebrating Imperial Russian war victories and nationhood. But St. Petersburg's esteemed manufactory was the leader in volume, quality and devotion to the idea.

But although the factory's creative cogwheels turned, the objects it produced fell into the wrong hands. The original mission had been to disseminate “Agitfarfor” far and wide in the homes of factory workers and collective farmers. The idea was that when they were eating their daily gruel, a glimmering portrait of Lenin would appear at the bottom of their plate. The Soviet leader’s face would remind the workers and peasants of their mission. The sobering slogan: “He who does not work, does not eat” on their plates would hammer the message in all too clearly.

The reality, however, was very different. The majority of objects were far too fine and too few. They found their way into the hands and homes of collectors before they could reach the working masses who anyway cared far more about the extremely meagre food on their plates than the colour of their dishes. In 1920, a desperate shortage of funds forced the Soviet government to export large volumes of “Agitfarfor” for sale at international fairs. Those revolutionary porcelains were immediately snapped up by western collectors.

The enlightening function of these artists, as so often happened with the most ambitious utopian artistic experiments of the early Soviet era, was overestimated. That failure helped to open the way for the forced imposition of a far simpler and more conservative style, Socialist Realism.

It left “Agitfarfor” to hang on the walls and rest in glass cabinets of wealthy Western collectors, the representatives of the new regime’s ideological enemies. It was a world where fine china had been thrown off its pedestal, seized by the people and reinvented, fused with ideology and technology, becoming an art that in theory could be used, be eaten off and be in everybody's home. It was a dream in which the White Gold of the East could be transfigured in the melting pot of revolution, emblazoned with creative and ideological fervour and fired to the highest of temperatures in order to create a shining porcelain world of hope.

An Alliance of the Arts. On the 275th Anniversary of the Imperial Porcelain Manufactory

St. Petersburg, Russia

25 December 2019 – 5 April 2020