Iveta and Tamaz Manasherov: all thanks to the teeth

From their first crush on a 19th century Russian seascape painter to creating avant-garde collections.

It is no coincidence that Tamaz and Iveta Manasherov have built a world-class collection of Soviet nonconformist art as well as the works of Russian and Georgian Avant-Garde artists while developing their dental care and medical laboratory business.

“Dentists had some of the largest and best collections in the world,” said Mr. Manasherov at the Moscow headquarters shared by the couple’s company and the U-ART Foundation.

“When top American dentists came to dental conferences, they would always show a tooth during their lectures and compare it to the work of an artist, pointing out how an artist looks at an object, how light plays on it from above,” Mr. Manasherov explains.

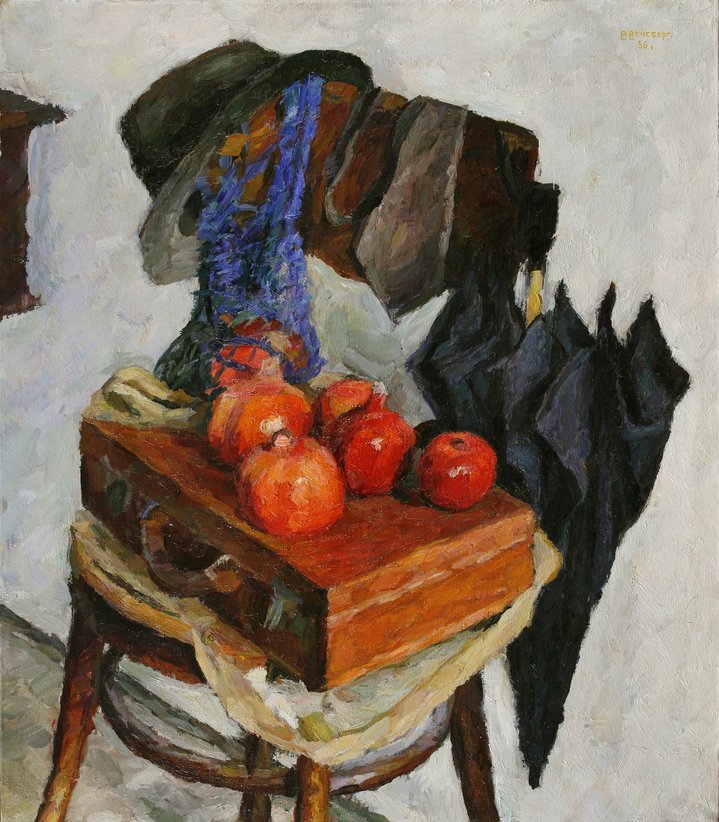

The couple were initially drawn to the works of an artist worlds away from what they now collect. Their first choice was of a popular Russian classic, 19th-century seascape painter Ivan Aivazovsky (1817-1900).

They acquired their first Aivazovsky for $20,000, but it was not a status symbol. As Mrs. Manasherov points out, “we bought a painting before we bought a car.” Today, they have only one of that artist’s works, kept as a memento.

The couple studied mathematics and were both raised in Tbilisi. As a result, they both became ardent collectors of the Russian Avant-Garde as well as its Georgian counterpart, which thrived in Tbilisi during Georgia’s short-lived independence after the 1917 Russian Revolution.

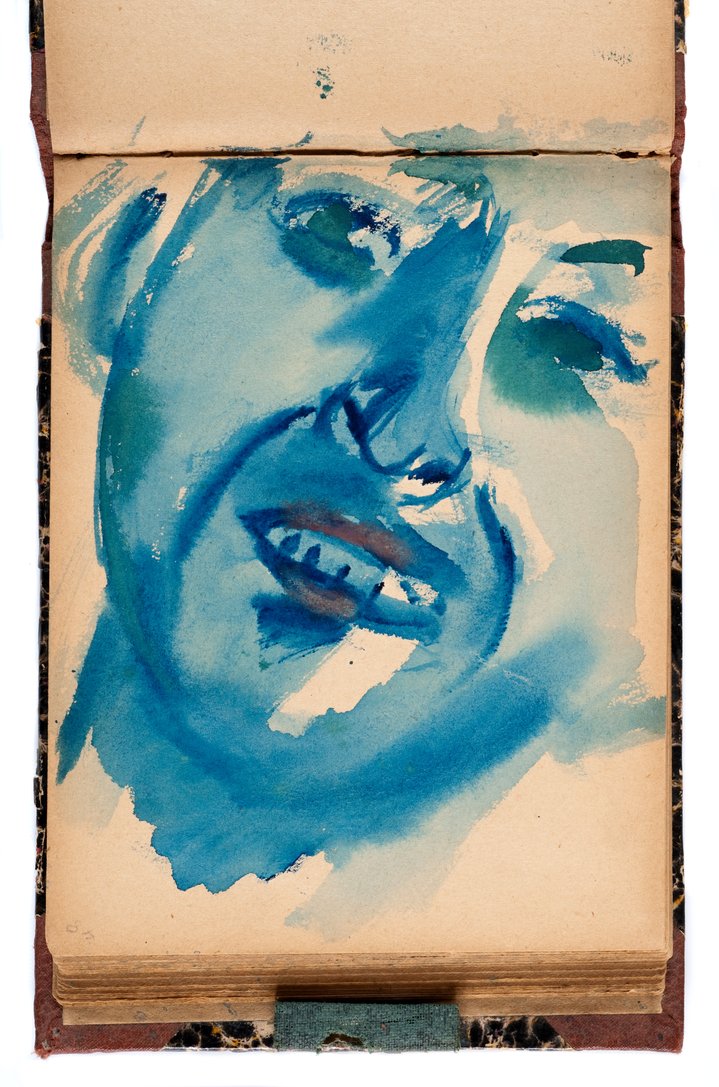

“We initially saw these works only in art books and museums and did not think we would see them in our home and live with them,” said Mrs. Manasherova as she tells the story of how they acquired works by Lado Gudiashvili (1896-1980), one of the key figures of the Georgian movement.

The Manasherovs organised an exhibition of Gudiashvili’s work at the State Tretyakov gallery in 2008, exactly 50 years after the Georgian artist’s last Moscow show.

The artist returned to Soviet Georgia from Paris in 1925 not realising he could never go back, and left many of his works behind as a result. Ten ended up in the United States in the 1920s and were eventually tracked down by the Manasherovs in Texas.

“I remember the awe with which when we received them here in Moscow and unpacked them at night, at 3 a.m. When you are waiting for something a very long time and when what you get exceeds your expectations, it is amazing,” she said.

In 2016, Mrs. Manasherova, who studied art history at Moscow State University, was the co-curator of a Georgian Avant-Garde art exhibition at Moscow’s Pushkin State Museum of Fine Art.

Although diplomatic and cultural relations between Russia and Georgia were broken off after a short war in 2008, over 90 works loaned by the couple helped make it an impressive show.

They have had their setbacks as collectors and philanthropists. Plans to stage a major retrospective of works by the Soviet nonconformist Mikhail Roginsky (1931-2004) fell through after disagreements with his widow, Liana.

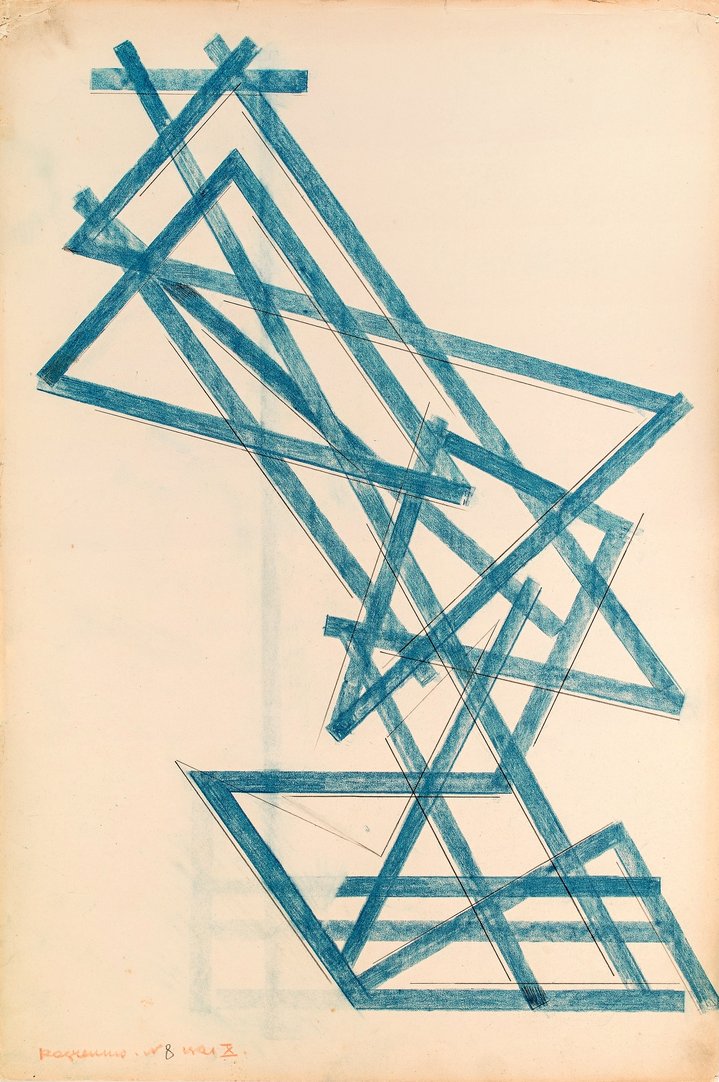

In 2008, the couple organised a major exhibition at the Tretyakov Gallery for another nonconformist painter forced into exile during Soviet times, Oscar Rabin (1928-2018). They tracked his works down for the show as far afield as Brazil. Meanwhile, Mr. Manasherov has focused on the origins and development of the Russian Avant-Garde, building up a collection of 35 works by Ilya Chashnik (1902-1929) and Nikolai Suetin (1897-1954).

“It is art that makes you think,” he said of the radical Avant-Garde. “It is art that is not immediately understandable to everyone.”

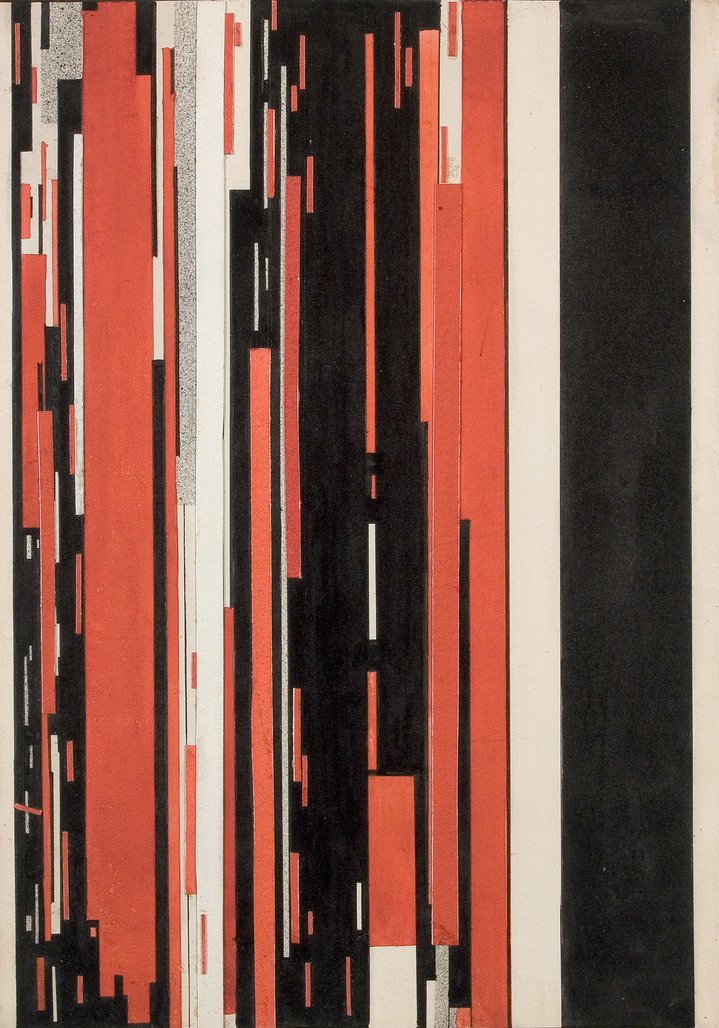

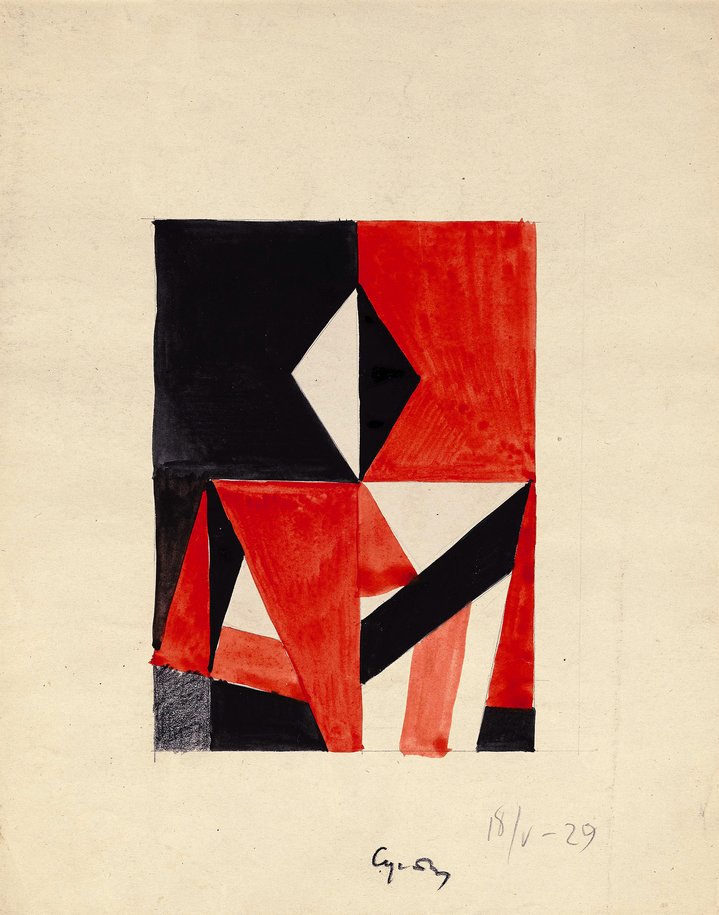

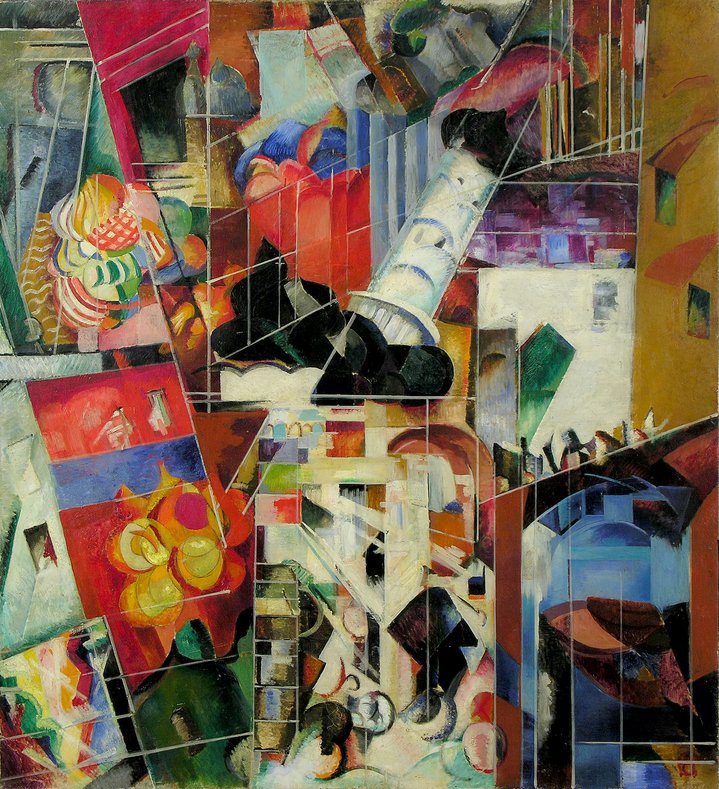

The couple deeply respect women artists of that time such as Varvara Stepanova (1894-1958), Olga Rozanova (1886-1918), Natalia Goncharova (1881-1962), Lyubov Popova (1889-1924) and especially Alexandra Exter (1882-1949), whose work led their collection in that direction.

“She was one of the few who acted as a bridge between Russia and Europe,” he said. “She was friends with Fernand Leger (1881-1955). She was also friendly with the Italian Futurists.”

Although the Manasherovs have over 700 works in their collection, they said they had no plans to open a museum. “A museum is a very high level,” Mrs. Manasherov said. “I don’t always agree when some institutions are called museums. I don’t think they always measure up to it.”

The couple is also striving to protect the market from an onslaught of fakes. “It’s awful, all those exhibitions with fakes,” complained Mrs. Manasherova. To fight counterfeits, “each artist must have at least two curators" and fakes must be publicly identified while the state has to take a stand, said her husband. “The purer the market will be, the more interesting it will become.”

The couple also believes that not enough has been done to highlight the revolutionary artistic impact created by the Russian Avant-Garde. “Russia should be leading the march of the Avant-Garde,” he said. “It is an absolutely Russian phenomenon. There should be more exhibitions with works of these artists, not as individual artists, but as a group,” he said.

For him, what is needed is to show these Russian works in the context of the Western Avant-Garde so that all art experts can see that dozens of “Russian artists were real trailblazers in this development and should be better known.”